About the author

More posts by Moderator

My parents tell me the only reason we weren’t a pilot family in the Advanced Training Institute (ATI) is the fact that I, their first-born, was only three months old when they applied that first year. Like many others who have shared their stories, my parents are wonderful people who sincerely love Jesus and wanted to raise their children to love Jesus, too. But when they bought into IBLP and ATI, they were sold a bill of goods.

My parents tell me the only reason we weren’t a pilot family in the Advanced Training Institute (ATI) is the fact that I, their first-born, was only three months old when they applied that first year. Like many others who have shared their stories, my parents are wonderful people who sincerely love Jesus and wanted to raise their children to love Jesus, too. But when they bought into IBLP and ATI, they were sold a bill of goods.

Over the past four years, I have begun to recognize and discard many of the damaging things I learned while still in the system. I’ve also begun to recognize just how much mind control took place under the guise of “ministry standards.” I’m learning about grace and Christian liberty—and catching up here and there on cultural references that used to fly right over my head.

I always loved to read, but while I was growing up my Dad called fiction “chewing gum for the mind,” which meant we read the bare minimum of qualified classics to graduate high school. I immersed myself in the non-fiction world of Christian biographies and American History, and only occasionally snuck some contraband fiction in the form of a (church) library book or two. As a woman, I was fortunate to have parents who believed in equal educational opportunity, so I attended college where I majored in nursing. I continued living at home once I got a job after graduation, and until the age of 27 I was single-minded in my determination to go overseas as a missionary. When I finally realized the person planning to go wasn’t really me—I was pretending in order to earn God’s blessing—I had the awesome opportunity to start fresh.

I did so with gusto.

My deep foray into the world of fiction began with J.R.R. Tolkien about two years ago, and from there I progressed through a wide variety of genres and styles. I have fallen in love with Madeleine L’Engle, Dorothy Sayers, G.K. Chesterton, L.M. Montgomery, and George MacDonald, while rediscovering the joys of C.S. Lewis, L.M. Alcott, Charles Dickens, Charlotte Brontë, and the like. Last summer, my church had a wonderful adult Sunday School class entitled “Reading Literature as Christians,” and thus I added John Milton and John Donne to my ever-growing Must Read list. I now routinely read multiple books per month, alternating between fiction and non-fiction, old and new, Christian and non-Christian. To say I have expanded my horizons would be a gross understatement.

This past fall I had the opportunity to visit friends who are ministering in Eastern Europe, and they suggested reading George Orwell’s 1984 to better understand the society where they currently live and work. I had picked up a copy in a used bookstore over the summer, but had not yet had the inclination to delve into dystopian fiction. Upon my return to the States, I jumped in.

Ten pages into the book, my skin was crawling.

The protagonist, Winston Smith, has taken a lunch break away from work and is sitting in his apartment, worrying about the Thought Police and what the “Big Brother is Watching You” slogan means, when George Orwell slips in a little detail about the telescreen: that marvelous device every Party Member has in his or her home that allows for continuous broadcasting of “information” and monitoring by the Thought Police. The device “could be dimmed, but there was no way of turning it off completely” (p. 6*). On page 10, the telescreen broadcasts “strident military music.” On page 29, I learned that the telescreen served as a universal alarm clock for employees of Big Brother’s various Ministries.

In a flash, I was transported back to my upper bunk on the twelfth floor of the Indianapolis Training Center. Though I only spent four weeks at the TC (a week in 1998 for the Counseling Seminar and three weeks in 1999 for Sound Foundations), I will never forget the way each morning began: a Sousa march played and the Proverb of the day read aloud over the speaker system at 5:30 a.m. The sound could be turned down, but it could not be turned off. The similarities were unnerving.

In Big Brother’s utopia, utter control by the powers-that-be is clearly an overarching theme. The only hint that perhaps the control is not as tight as Big Brother would wish is a curious description of Winston’s rare and brief interactions with a character called O’Brien. Early in the book, Winston and O’Brien have never exchanged words, yet Winston feels that O’Brien shares his unorthodox political leanings. In the moment when they first make eye contact, “…there was a fraction of a second where their eyes met, and for as long as it took to happen, Winston knew—yes, he knew!—that O’Brien was thinking the same thing as himself” (p. 16).

Looking back, I wonder how I missed that this concept threatens the leadership of closed systems. I remember Mr. Gothard talking about this phenomenon on multiple occasions. It was something to be avoided at all costs—the recognition fellow rebels have for each other based on eye contact alone! Those in rebellion, Mr. Gothard claimed, could and would seek each other out simply by seeing each other. If you happened to be in the vicinity of such a rebel-gathering, the judgmental glances would fall on you as well. And since we were taught that external appearance was a clear indicator of the condition of one’s heart, I learned quickly to judge whether or not I could safely make eye contact with someone based on how they looked, dressed, or acted. At ATI gatherings, I was extremely guarded. How could I, in good conscience, make any friendship with anyone who dared to wear a skirt with flowers on it? How could I associate with another girl who was wearing sneakers—or worse, open-toed sandals?! How could I talk to someone who talked to boys and not be implicated right alongside her for being a flirt or a rebel—or more unthinkably, talk to a boy myself? It was impossible, so I kept my ministry smile on and hardly opened my mouth except to utter approved Institute phrases.

“He had set his features in the expression of quiet optimism which it was advisable to wear…” George Orwell writes of Winston (p. 8). “In any case, to wear an improper expression on your face… was itself a punishable offense” (p. 54). While in ATI, I learned the importance of having an impenetrable “ministry mask”—a constant “energy-giver” smile. Of course I didn’t see it as a mask while wearing it. I just knew that without the proper facial expressions and expected verbal interaction, I would get in trouble and thus be ineligible for God’s blessings. That was a serious, scary threat to my first-born, conformist, desperate-for-acceptance tendencies.

Perhaps the most damaging parallel aspect within 1984 and ATI, however, was doublethink: a 1984 Party construct of “Newspeak” (the idealized, neutral, minimalist language that was the official form of communication within Ingsoc) that roughly communicates the concept of containing two opposite, mutually exclusive views in the same thought or word. Within ATI, this concept could very easily be illustrated by a superficial look at grace.

While the standard definition of grace in ATI/IBLP is “the desire and power to do God’s will,” Mr. Gothard would also claim that grace is a free gift and not something we could earn. I never heard the definition of grace as “unmerited favor” until I was 21. That’s when the serious cognitive dissonance set in. God gave grace freely, I learned. Grace was supposed to be what enabled me to find and do God’s will—meaning to obey, submit, and love. Yet often I did not feel obedient, submissive, or loving. If God gave grace freely, why did I struggle to exercise it? ATI taught that any failure to obey, submit, or love was my fault, because I did not have the right desire to do God’s will. In fact, anything that went wrong in my life was probably my fault. But where, then, was God’s free grace?

Above all, the powers of 1984 and ATI sought to keep three distinct groups of people separate: in 1984, the groups are referred to as High, Medium, and Low, represented by Big Brother’s Inner Party, the Outer Party, and the proles (or general public), respectively. ATI had Mr. Gothard, parents, and students. In both dystopias, the aims of these three groups are entirely irreconcilable. The aim of the High is to remain where they are. The aim of the Middle is to change places with the High. The aim of the Low, when they have an aim—for it is an abiding characteristic of the Low that they are too much crushed by drudgery to be more than intermittently conscious of anything outside their daily lives—is to abolish all distinctions and create a society in which all men shall be equal. (p. 166)

So rather than leave it to chance, Big Brother and Mr. Gothard instituted rigid guidelines that made any change of position impossible. Parents were constantly in competition with one another, and students were far too tired to think beyond when they might next be permitted to rest.

But it was all for a purpose—or so we thought. Demands to live up to Mr. Gothard’s standards were “softened by promises of compensation in an imaginary world beyond the grave” (p. 167), should we be able to keep them. In other words, God’s eternal blessing was tied to our performance of a set of man-made rules. Scripture itself was misused repeatedly to keep us from questioning either our authorities or the outside world. “Indeed, so long as they are not permitted to have standards of comparison they never even become aware that they are oppressed” (p. 171).

I could go on. I could talk about how every minute was scheduled at any ATI event. I could draw parallels between the concept of courtship and the Oceania Ingsoc Party line on marriage (even the slightest sign of affection between a man and a woman before their relationship was approved by an outside committee would mean they would never be permitted to see each other again—and I’m talking about the book, not ATI). I could point out that in order to live within the system, you really had to be dead inside—and if you insisted on being alive, you knew it was at the cost of an earlier death. I could dig into the pain of forced confessions—whether the acts were committed or not, and knowing that there was no escape from shame and other consequences, no matter how extensive (or truthful) the confession.

But just one more observation—and this one straight from the book, which was published in 1949:

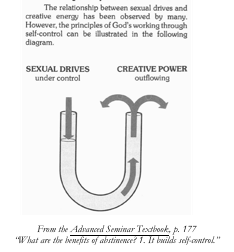

Unlike Winston, [Julia] had grasped the inner meaning of the Party’s sexual Puritanism. It was not merely that the sex instinct created a world of its own which was outside the Party’s control and which therefore had to be destroyed if possible. What was more important was that sexual privation induced hysteria, which was desirable because it could be transformed into war fever and leader worship. The way she put it was: “When you make love you’re using up energy; and afterwards you feel happy and don’t give a d*** for anything. They can’t bear you to feel like that. They want you to be bursting with energy all the time. All this marching up and down and cheering and waving flags is simply sex gone sour. If you’re happy inside yourself, why should you get excited about Big Brother…?” (pp. 110–111)

The banishment of every sexual thought, of every hope of marriage, of any chance of normal male/female interaction was clearly the goal within ATI. Singleness was a sign of complete commitment to God—and the Institute. Mr. Gothard was revered for his choice of holy singleness.

1984 is a depressing study on what goes wrong when power and control are summarily handed over to one person, without thought or question. The last third of the book chronicles the vicious process of Winton’s “re-programming,” ironically at the hands of O’Brien. Big Brother wins; Winston’s life becomes nothing more than an animatronic shell dedicated to the adoration of the force that destroyed him.

ATI had its own facilities for reprogramming wayward students; we referred to them as “Training Centers,” and one considered it an honor to be invited to serve in any capacity. The stories of Training Center abuses perpetrated in the name of Christ which have surfaced on Recovering Grace are nothing short of sickening.

How have so many of us, then, avoided an utterly shipwrecked faith? The setup was perfect for the absolute disintegration of our lives. Many souls were shattered; proof of that is emerging daily. Label us bitter if you will, but my response as a voice within Recovering Grace is common: I only want to spare others the years of spiritual paralysis I experienced as I unraveled the false teachings of Mr. Gothard, IBLP, and ATI. For me, meeting the real Jesus has been a matter of eucatastrophe. The word, an excellent one coined by J.R.R. Tolkien and defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as a sudden and favorable resolution of events in a story, encompasses the idea of “grace that cannot be counted on to recur.” My story has not ended like 1984 because I have encountered real grace, and it has changed my life.

I no longer think that ATI was founded in the year 1984 by a mere coincidence. I no longer think the application of the “Basic Principles” is original to Mr. Gothard. I can no longer pretend ignorance to the ultimate aims of the Institute—not when there is so much evidence that power and control were the driving forces behind the seminars, the programs, the “ministries.”

I wasn’t just born in 1984: I lived it for decades.

WAR IS PEACE

FREEDOM IS SLAVERY

IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH

—————————————

*Page numbers refer to the ©1984 Commemorative Edition with Preface by Walter Cronkite and Afterword by Erich Fromm.

Just....wow. Well, maybe, just maybe it is possible to summarize large parts of what IBLP is all about by saying "sex gone sour". Maybe in the new re-org. it can be the new acronym: SGS

That was my exact thought. wow.

My gut hurts right now. I am just stymied at the similarities. Totally unreal in likeness. Thank you, Susanna, for speaking truth. I wanted to write "thank you, I think" because so many memories came flooding back with your review of many of the teachings/worldviews of IBLP/ATI. It is difficult to go there, still. But, thank you for all of the time and thought put into this.

Rejoicing with you in your new found walk of grace!

This is an amazing parallel, Susanna. Wow!

I was at the ITC in 1995-96, and I definitely experienced the "Big Brother Radio" (BBR) that Gothard thought was so cool. "The device “could be dimmed, but there was no way of turning it off completely” from the “strident military music.” Yep. That was our experience every morning! You could never turn the radio off completely. The first minute or so of the Sousa wake-up music was full blast---the volume could not be changed on it. After a minute or so (I can't remember exactly, I was never fully awake enough to figure out the system), you could adjust the volume, but not fully turn it off. So the "volume control" was a joke. It gave you the sense of being able to control *something* but in reality, it gave you hardly any control, as the options were medium to loud, but never completely off.

Every now and then one of the guys would figure out how to disable their radio (which was literally installed in the walls), and boy, the wrath of all leadership fell upon them! That was the ultimate crime against BBR! LOL

Just another day in the life of IBLP Training Centers...

Susanna, what a gifted writer you are! Have you read Brave New World? What parallels can you make of our modern society to that book? I would anticipate your view.

"Brave New World" is on my bookshelf and my to-read list for this year... We shall see what sort of writing it brings forth! (Thanks for the encouragement!)

I had a parent leery of fiction because it wasn't true, but thankfully, though my reading list was highly censored, I was still allowed to read copiously. Interestingly enough, fiction, though supposedly "not true," is a way to present the truth, as you discovered with 1984. Storytelling is a powerful way to communicate and is often more compelling than a plain listing of facts.

I loved reading the connections you found between the book and ATI, and, from another first-born, approval-seeking conformist, I am so glad that you discovered God's amazing grace. It's so much better than constant striving to keep man's rules.

Jesus's parables were fiction, right? Fiction communicating truth.

We were taught (and I think this cames from the institute) that the parables were true stories that Jesus was telling that had happened at some point because Jesus is truth He would only speak truth and so they had to be true.

Yes, I guess there are some who think all the parables are true...I think you have to stretch to hold to that (sort of like believing the wine Jesus made from water wasn't alcoholic because "alcohol is evil" and He never would have made it as such).

Some interesting comments on the parable topic here:

http://www.baptistboard.com/archive/index.php/t-38945.html

study the word Yayin before launching into the wine debate. Wine is a mocker.

@Grateful: I'd be careful about constructing my entire theology around proverbs... sketchy, imo. would all 138 uses of 'yayin' through out the bible tell me that wine is ALWAYS and must be, a mocker ?? I do not know of any orthodox jews who believe that, fwiw. I'd start with how Jesus dealt with wine, and work backwards into the OT.

"because Jesus is truth He would only speak truth and so they had to be true."

Yeah as in plucking out one's own eye! See any one-eyed believers lately?

John 2 9-10

9 and the master of the banquet tasted the water that had been turned into wine. He did not realize where it had come from, though the servants who had drawn the water knew. Then he called the bridegroom aside 10 and said, “Everyone brings out the choice wine first and then the cheaper wine after the guests have had too much to drink; but you have saved the best till now.”

If someone believes that Jesus was turning water into grape juice, please take a look at these verses. If it was non-alcoholic grape juice, no one would be drinking "too much" of it. That is just not something people would do with grape juice. Nor would it make sense that the cheap stuff was brought out after they had had too much to drink. When you drink too much alcohol, you can't tell anymore that you are drinking cheap wine. The wine in Scripture, was really wine.

The wine is really grape juice teaching makes no sense in the context of Scripture. I've never heard of a serious theologian who subscribes to that.

If you are convinced that GOD is 100% against alcohol, this is where you are pushed into a strange theology. God just isn't as fussy on makeup, dresses vs pants, alcohol, strong bass beat, etc...

hey look, I don't want to take away from a great article - nicely done, Susanna (try Animal Farm next :)) - but alcohol has and will continue to destroy a kabillion more families than BG's ministry ever can and will. Wine is a mocker.

Oh boy, I am gonna jump in here because I also come from a long line of alcoholics. My father, brothers and extended family members were addicted to alcohol. I could convey more incidents then I care to remember of the affects drinking had on those people.

You may technically be correct as to the exact numbers that BG ministry may have since his personal ministry has operated for less then sixty years. However the ideas/principles and abuse of authority have been perpetuated since the fall.

One only need to glance at the history of ‘the church’ to find misuse of power through the ages. The misuse of power is idolatry. It is putting oneself in the place of God. Every time I used my authority as a cloak for my anger, impatience and demanding nature, I misrepresented God and supplanted his character.

I personally believe the power of the tongue and misuse of authority as perpetuated by IBYC, IBLP/ATI and countless other elders, leaders, ministries of the gospel have caused as much harm ( has been that idolatry…. Worship of the god of self) to the souls and spirits of those seeking truth as alcohol.

I really do not want to be contentious; I have personally had my eyes open to how a particular sin (I am talking about in my own life.) can be a cover for hideous offense in countless other areas. That reality caused as much harm to others from me (I had sworn off alcohol because of it’s influence and destruction ….) through my justifying my authority. In all the years I was raising my children , I did not drink a drop. Oh, but the damage done from my lips to the souls of those entrusted to me by God was enough that I deserve a millstone around my neck and to be flung into the sea.

The tongue and it’s sin under the cloak of authority has proved to be as harmful to the souls of men as alcohol. BG is one of countless offenders, myself included. My intent is not to be harsh. It is particularly of concern to me that we guard against an external evaluation. 1 Tim. 5:24. The sins of some men are quite evident, going before them to judgment; for others, their sins follow after.” To my shame while I held up my children’s obvious disobedience, my own sins were to follow after. Well , I at least was blind to my own hypocrisy for years. Through the enabling power of His Holy Spirit, He gave me the ability to see my ugly self.

His grace is sufficient. Oh, that we would examine ourselves, repent and represent Him well to His honor and Glory!

Psalm 130:3. If thou, LORD, shouldest mark iniquities, O Lord, who shall stand?

I'm trying to swear off rabbit trails, and (like yourself) do not want to deflect from a great article. high calorie and fried food kills more than alcohol, they get banned next ??

I won't follow the bunny on this one further, promise.

sorry I posted the sign pointing toward the rabbit trail. :-/

yes, let's not continue the "hops"

nyuck, nyuck, nyuck

@Libby : very well said

@grateful: funny funny bunny

Sexual addiction has destroyed many. That doesn't mean sex is evil.

The issue is never alcohol, or sex, or fried food, or television...the issue is the heart. It is always the heart.

I also hated the BBR... now that's a club I'll join! :)

I really liked Sousa's works prior to being under BBR. BBR ruined it for me.

Wow, yes, the parallels here are staggering. Thank you for writing this. A system of control is obviously not exclusive to ATI, but wherever it is found it dehumanizes people. What hurts the most is that, for us, this system was promoted in God's name.

I spent a combined total of about 6 months at various Training Centers. Oddly enough, even at the time some of us young people would secretly joke that the Institute was an "Institution." Perhaps subconsciously we recognized that something was amiss, that Gothard was just a man, and that the Christianity presented to us was full of hypocrisy. But we were essentially powerless to speak up against the dehumanizing features of the system or pursue a life-giving, grace-filled Gospel. Until now.

And they write us off as bitter.

Haha! Yep. Bitter, hurt, angry... you bet! :)

Susanna, every time I read this I get shivers. It's deeply uncanny how descriptive "1984" is of ATL and your experiences therein. I'm delighted beyond words to witness God's eucatastrophic intervention for your heart---the one thing that all the Big Brothers in the world can never avoid nor defeat, nor keep out of the lives of their victims---for we are His, and He always comes for us to strike off our shackles and bring us out into His wide green spaces.

Dearest Kay, You (and your family) have been such a HUGE part of my own little eucatastrophe. There really are no words that say THANK YOU sufficiently. Your friendship means the world to me!

Well done! Very insightful. Thank you for sharing!

Susanna, this is so well written! I remember reading this book in 1984 when I was in high school and thinking, "So glad that is just fiction!" I sadly have had to retract that naive thought too many times since then. As I read everything you wrote, I am again moved to tears and grateful for God's allowing our paths to cross, dear one. I pray for you and so many others who are recovering quite often. Who would ever have guessed that a mission trip to Zambia in 2010 would help to bring healing to many hurt by Gothard here in our own country? (I have experienced healing, too, since by reading everything in Recovering Grace and realizing how much I was impacted by my dad's buying into Gothard's lies from the seminars in the late 70's, I now know how to better reject the legalistic garbage that tries to still creep in my thinking.) God is amazing in how He chooses to connect the healing dots in our lives!

Oh Ruth Ann,

How well I remember that cold Friday night in November 2011! I was leaving your home after a lovely conversation - mostly about going overseas - and you very gently handed me three books on my way out the door. "I think you should read these," you said. What a roller-coaster that started! Thank you for the pivotal role you've played in my life! You were the key that unlocked healing for me. Love you so very much!!

I read "1984" for a class early in my college experience. It was very eye opening.

:Thank you for an amazing and brilliantly written article, Susanna. It is a must read for any recovering, ex-ATI parent. I am personally very grateful for your honesty and thoughts, as I have asked God to help me clearly understand how ATI "felt" from my childrens' perspectives. I know how "I" feel about making such a severe error in raising them, and all the reasons I thought it would be a good and safe program to be involved in only to find that it is indeed one of the most dangerous and harmful things we could have done to them, but I have realized that it was totally different for them, growing up with the faulty teaching and perception of God and Who He is, because it was all they ever saw or knew, and I am realizing how TOTALLY deceptive it was for them and how it was the only world they knew, and all they missed and felt. We got some good things from it, I suppose, but it didn't allow them to become the people God created...they were molded and re-molded into someone's idea of whom they should be, and thus not able to develop as they should have. Your article has given me the clearest glance of all they experienced and how they felt. Thank you so much, and although it is painful to see and feel these things, I am so thankful we are being freed to become the people God created us to be...He promises beauty from ashes, and I believe Him...otherwise it would be difficult to go on sometimes in this journey, although the blessings of freedom are so rich, even with many regrets about where you used to be. Thanks to RG for their dedication to making truth known, and for each person who has afforded us a look into their deepest hurts and their very hearts. Your words are bringing healing and truth to masses of people, caught in something they never realized was a trap. I am grateful.

I certainly identify with your experience.

For myself, I must add that my own understanding of family/authority was influenced by my thoroughly German heritage and authoritian non- Christian parents. Having become a Christian in 1971 as a young mom with all that background, when I first attended an IBYC conference in 1977, it fit right into my own understanding of authority.

Godfaithfully worked in me, I must say. His Holy Spirit repeatedly spoke to my own spirit "The anger of man does not achieve the righteousness of God" Jas 1:20 NASB. For years I justified my own sin and hid behind my authority as a cover. So often I required unquestioned obedience to my authority all the while I was disobeying God's command not to exasperate my children.

We attended serveral conferences encouraging many to attend.... even paying for people to go. However, thankfully while attending our first Advanced Seminar my husband and I finally had "pause". Several parts of the advanced training just seemed over the top.

It took many years for my mind and heart to be willing to look at myself and fully realize my unloving, demanding spirit to my children. Thankfully, our sons have forgiven us; a daughter still remains separated from us.

As I look back upon the IBYC .... We last attended a seminar immediately after the revelation regarding Steve ... One of my greatest lessons learned was that I never gave my children a voice. That old " children should be seen and not heard" line was the most destructive thing. When you demand absolute obedience without question there is no grace afforded.

Sadly, many parents fell into step with BG teaching because of a need to control. Yes, the original intent may have been from fear because we wanted a fool proof outcome. Part of my sin was pride because of what people might think. Yes, I was baited, but my own sin feed right into 'the system', too.

RG is a means that God is using to "give voice" to so many. May God's Grace continue to being healing to all those harmed by IBYC. IBLP / ATI .

What were we thinking?

If you want to reconnect with your daughter, I can tell you what would work for me (I'm a daughter that has drawn a few "do not cross" lines with my folks).

What I want more than anything is for my parents to initiate an original, pre-meditated apology stated to my face and I would also like it in writing so I can review it and consider it later as I muster up as much understanding as I can find. I don't want pressure to forgive, and I don't want pressure to immediately involve them back into my life. I don't care to discuss every single thing that they did, I just care about a fairly all-inclusive apology, followed by a significant amount of time to validate it.

I would notice if they stuck their necks out, scrapped their pride, and left the ball in my court. For me, TIME is the biggest element in an apology. Time is what reveals sincerity and permanent change. I can only imagine that is must be heart wrenching to be a parent on the other end, waiting for that apology to be validated and fully received.

Forgiveness is one thing - but reconnecting and rebuilding relationships is a whole other ball game. The latter isn't as "easy" and takes a lot of intention and effort from both parties. If one party isn't doing the work... well, it takes two to tango.

It sounds like you're in what I call the "prove it" stage: after an apology has been issued and change has taken place, but has not yet been fully actualized by the apologizEE. :)"Proving it" is a long and lonely trail through the desert.

May peace be with you as you go down that path for your daughter.

Thank you, Brumby

Perhaps we are in the "prove it" stage.

Strangely, we adopted our daughter at the age of ten years soon after our last seminar attended. Years later we did hear of families who sent adopted children back. We never entertained that teaching. So much goes into our stories/journeys.

After three years of thinking we were making progress, in 2006 things went badly. I have examined my communications and conversation often and with tears. We certainly employed some of the tactics you mentioned. Ugh, by prayer and His grace we continue to look, and wait for her and upon The Lord. In 8 years , we have had three face to face contacts... A few emails. Though she is no longer hostile to us, she does continue to express continued blame to our account in the limited contact she has with her brothers.(I am certainly guilty as charged. So, in expressing this I am not denying the blame attributed ... I suppose I could say that she is not yet willing to forgive, but, that sounds ungracious and seems to attribute a type of mocking accusation . I do not want to convey that in any way.)

Wait, I say, upon The Lord.

Therapy was an intense accelerant on my path of healing. I hope she has or will give therapy a shot. You can't fix it all yourselves, but you can do your part. The important thing is that you do (have done) your part. Hope is a powerful pillar of support while she processes your change and her past.

"Strangely, we adopted our daughter at the age of ten years soon after our last seminar attended. Years later we did hear of families who sent adopted children back. We never entertained that teaching."

When I hear about the results of his teachings about adopted children, it makes me so sick to my stomach. I have the booklet that encourages adoptive parents to send their children back into orphanages. There are many very wrong things about IBLP. Its teachings on adoption are certainly amongst the darkest of their teachings.

Along with all of the stories of pain, we often hear some "success" stories. A person use to drink and smoke pot, and then went to the basic in 1975 and their life was turned around and so forth. Usually, there seems to be the caveat, "of course, we did not accept all of the teaching."

The problem is, some did. Some accepted everything that Gothard taught and actually sent their adopted children back to orphanages. The family that was supposed to be your forever family, turning their back on you because of the teachings of this man. It's sick beyond words. Twisted evil teachings have real world consequences- if you were one of those orphans, these teachings could have caused you to lose your family, when you needed them the most.

Libby,

I am very glad that you did not accept this part of the teachings and I pray that your daughter accepts your apology and that you can have a restored relationship with her. That separation must be a very hard thing to deal with.

Bill Gothard was very discriminatory against adopted children and especially did not want families that had biological children to mix adopted children into the family. I am wondering if in your time in IBLP, if your daughter felt that discrimination from the organization in any way and perhaps it added a layer of pain that was not present with your other children?

Prayers for you and your family for healing.

Kevin,

Thank you!

Your question regarding our daughter's perception is legitimate.

I have to honestly say that the majority of the blame lays at our door. The pain is that we did not 'see' what she really needed. Employing a system with guaranteed results was much more palatable at the time then looking at my own heart. She needed grace; I gave her Law and guilt and demands instead of the love she needed. She often felt so frustrated. I have expressed that to her; that I understand that she tried and it was never enough.

Please continue to pray that God will minister healing to her broken spirit. That He will send a minister of His grace to her that she may be healed!

Libby,

We, too, are an adoptive family. There are extreme issues with the one size fits all approach of 9 steps to this, and 7 steps to guaranteed success, ect. As wrong as this approach is for biological families, I think even more so with adopted children. You could be dealing with things such as Radical Attachment Disorder, RAD, and trying various steps that are supposed to work for all children, while totally missing the mark. The simplistic steps that are taught ignore differences between individuals. They will not work for everyone. I have to wonder if Bill Gothard's anti-adoption views were partly formed by how poorly his methods worked for adopted kids.

Please don't be too hard on yourself. You and your family were victims. You are brave and humble to apologize and it is very clear that you love your daughter very much. My recommendation would be to keep communicating to her how much you love her, even if it has to be with cards and letters. Just keep sending her that message and keep praying for healing for her and your relationship with her. Even if she does not respond, believe that it is meaningful to her to hear from you every time you tell her how much you love her.

Grateful to both Libby and "anonymous" above for their honest words about themselves. I will remember what you have shared as my little 1-year-old son grows older: "So often I required unquestioned obedience to my authority all the while I was disobeying God's command not to exasperate my children." I know I need to keep a constant watch for this in my own heart. Your stories, and even more so your humility to show what God is correcting in you, are so helpful and encouraging to me. Thank you.

I have been waiting so long to hear what you just said. As a kid that came through the ATI/IBLP "system" all I want to hear from my parents is "Almost everything we taught you was wrong, and we were motivated by fear, pride, and needing a sense of control." When my family was in the "system" it felt so wrong for so long, but any objection only labeled you as "rebellious" and made your life worse.

Thank you for loving your children enough to look at life from their perspective and realize the challenges this "system" created for those who were processed through it. We can only overcome our challenges once we have a realistic perception of what they are.

Will May,

One of the greatest obstacles for our daughter is the faulty image of God that we presented to her. Combine that with the horrors she faced in the social service foster care system before we adopted her at ten years old and it was a recipe for disaster. Instead of giving her a loving image of God, I reinforced her perception that she was on her own and had to survive by any means possible while still being a child. My pleas to her for forgiveness and stating that I did indeed misrepresent God to her are something that she simply cannot grasp. Her whole life experience told a different story to her soul. God forgive me, I failed her!

I pray you can see God in His loving, forgiving, gracious truth. May He be to you what every human has failed to be! He is able. My hope is in His ability to touch our souls and bring truth, hope and healing to our brokenness.

Blessings to you!

You've chosen great authors as your first fiction! Nearly all of those are books I've carried around since college.

I attended IBLP in 1998 when I was going through a major life crisis. It had a profound impact on me. For a couple of years, I lived a squeaky-clean life, drove the speed limit, took shopping carts back to the store instead of leaving them in the parking lot... And then after a couple of minor moral lapses I dropped into serious depression as I realized how incapable I was of living by the Law. I attended IBLP again to try to snap out of my depression, but it all sounded hollow now: requirement upon requirement, rule upon rule, anecdote upon moralistic anecdote.

About five years ago I joined a men's group that focused on grace, and for the first time really internalized the Gospel of regeneration and full acceptance. It was permanently life-changing. It is much easier now to detect manipulation of all kinds, and to see to the incorrect beliefs at the heart of people's struggles.

I want to thank you and so many others for sharing. I think telling your story is way to help heal yourself and others. Thank you so very much!

I came across this website a few days ago and it has opened my eyes to much of the way that ATI is still wrongly (there is also some good) impacting my life today. I really do not talk about my family's years in ATI, partly out of fear, embarrassment and so on. My story is not as scary as yours and many of the others. I spent sometime "serving" at ITC in 93 and things were not as strict as many you sadly went through. But, I was also one of the annoyingly "good ATI girls".

As others have pointed out, 1984-type methodologies and structures also exist in cults such as Scientology and Mormonism (especially the fundamentalist branches). But this should not be true among Christians! We tell unbelievers that Christ offers joy, peace, love, and freedom, then legalists burden the new believers with worry, guilt, judgment, and imprisonment. "It is for FREEDOM that Christ has set us free. Stand firm, then, and do not let yourselves be burdened again by a yoke of slavery!"

wow - this is amazing. can hardly believe that the first time I am on this site I see a brilliantly written work by one of my favorite people. thank you, Susanna, for everything. For your courage, your leadership, and your love. You give so much and have, by the grace of God grown so my in your Faith. keep up the good work. I am so honored to have you as a sister. Love you so much.

I can't believe *today* was the day you first came to RG... God works in mysterious ways. Love you SO much. And continuing to pray for your healing. Can't wait to see where God takes you!!!

I can't help but think if BG also read 1984 and used the same principles in his "ministry."

Just when you thought that the writing of RG couldn't get any better...

To those who think that RG is nothing but a group of angry people airing their bitterness: the excellence of the expression in this article and others like it is a fitting protest against the ignorance (if not outright malice) of such baseless accusations.

Bra-vo. Standing O here.

Jim K.

and the perfect protest against mindless, drab, navy and white groupthink: creativity and imagination, the outflowing of souls that are really free and really human; well done Susanna W. and RG

Thank you so much for your encouraging words, Jim. K. I must say this was published with much fear and trepidation on my part - but at the same time, I *knew* it HAD to be written and shared. It's all part of the adventure of healing.

I'll join in that ovation! :)

"When I finally realized the person planning to go wasn’t really me—I was pretending in order to earn God’s blessing—I had the awesome opportunity to start fresh."

I immediately connected with that statement, and your entire article. I have read 1984 as a school assignment way back when. I would like to get it and read it again, now that I have come out the other side of living my own 1984. Thank you so much for sharing.

"...a boot stomping on a human face, forever," indeed... Wow. Chilling. An exact match between the two's ideology on sexuality and energy! Very well written! Thank you.

Another fantastic article grabbing the capacity and potential and harnessing capabilities,of someone that was created in God's Image,almost destroyed by religious man,was delivered by the only ONE who could deliver,and became eloquent,to warn and shake us to our senses.Thank you again and again.May I recommend two more authors to wrestle with.Alexander Solzhenitsyn,and Elie Wiesel.With Solzhenitsyn's Christian influence comes the shadow of the Orthodox church to which I'm attracted to as an outsider,may always be.But I hope fervently not to the Christ.

After stumbling on RG several months ago, I have read every single word published. Yours is absolutely the BEST, Susannah. You are a skillful writer and a good thinker. My husband and I attended our first basic seminar, to be followed by many more) in 1972 in Washington DC. We were young marrieds, just out of college, with our first child only a year old. We were also new to the teaching of God's Word, and the foundational teachings of IBYC, such as having a clear conscience, forgiveness, moral purity, purpose of authority, purpose of suffering, were life changing for us. It is both heartbreaking and confusing how it all morphed into something unbiblical, twisted, and dangerous.

We thank God that we never got into the style of homeschooling nor the materials that Gothard sold, though we did homeschool. And we had the miraculous discernment from the Holy Spirit to eschew teachings that we "somehow" recognized as off base. I suppose it was because we were in a solid Bible-teaching church, and we were being anchored in Truth.

I was very interested in your comment about Gothard being revered for his holy singleness. That was a teaching that we just couldn't buy; I constantly struggled with it, being overwhelmingly grateful for my marriage to an amazing guy. We had dated and married in the late 60's, and even in the 70's we knew of no churches that were anti-dating, selling the BG nonsense that discouraged such socializing. It was apparent to me that his ban was wholly unbiblical. God DESIGNED us for marriage, for intimate relationship, for family to contribute all that marriage brings to society. Dating was a path to that, and not all who dated ended up in immorality. I suspect that this rogue Gothard teaching had a weighty influence on the I Kissed Dating Goodbye campaign later in Bible centered churches. Our young adults have been suffering under that for 20 or 30 years now, and are still pathetically reluctant to marry at all! What a shame.

I post selections from the RG site on my FB regularly, and this one today has already been posted. May God grant to MANY OTHERS recognition of the IBLP (et al) errors so that they, too, can experience the Lord's amazing grace that brings true freedom to love and worship Christ Jesus our Saviour and Lord. And may He, in His timing, disassemble this ministry. The foundation became too faulty, I believe, to be retrieved.

Dear Linda: My wife and I had a similar experience in the late 1980's. We were in our first church, and attended at IBLP seminar. The teaching was powerful and instructive, yet, I felt in my spirit that there was something very wrong with it. Now, over 20 years later I am seeing just what a cult-like organization BG and IBLP is. I thank God that we did not enroll our children in the ATI in the 1990's.

Kevin: I did not know BG taught against adoption. Can you imagine our Lord doing that to us? "Just send the adopted kid back--I don't want him?" Just who is this BG monster? I hope more and more people speak up. As BG used to say, let the truth not be held back (ROM 1:18).

Guy,

I agree. It is so anti- Biblical, so anti-Jesus, to teach the abandonment of adopted children. We are called to help orphans, and we ourselves are adopted by Christ. What better way to help orphans than to give them a loving family?

In the booklet he uses anecdotal stories of families that sent their children back, suddenly blessed by financial rewards that were unexpected, suggesting God's favor for their decision:

This is the story of a family that adopted a one- year old baby, then, following advice of counsel, abandoned him at age 6, sending him to an out of state orphanage:

I quote: "Within two weeks after his arrival, we began a downward spiral financially that was unbelievable."

But, just look how God blessed them, or so he would have us believe, after they sent him away:

"Within two weeks after our son left, it was discovered that one of the companies my husband does business with had been holding back money they owned. The check they sent almost totally covered the amount my husband's business had gone into debt! (It was many thousand dollars.) Other things have happened that are helping us to get our personal finances in order."

Basic Care Booklet 5, pages 44-46

How despicable!

And billy is always using stories of nameless people and very few specifics so the stories and facts can't be checked out----happens time and time again.

Greg,

yes, there is no way for one to verify the thousands of anecdotal examples he uses, to "prove", the success of his teachings. How convenient. He also has a habit of referencing studies that ostensibly occurred that support his views, but I don't believe I have ever seen an actual study cited in a footnote, or noted with specifics, such that it could be looked up.

For example, in one of the sections on page 17 of the adoption booklet (really the anti-adoption booklet), he teaches, incredibly, that adoption promotes abortion. His logic is so twisted, that it could be a great case study for a logic class doing a section on logical fallacies. Of course, the study he uses as the key data for his off the wall conclusion has no reference, no date, no name of the institution, nor names of those who conducted it, so it can't be verified.

Actually, contrary to the IBLP teaching,for women considering abortion, learning that there is another option, and that there are families that would happily adopt their baby is something that encourages many to not to have an abortion and to see there pregnancy through.

http://www.americanadoptions.com/pregnant/deciding_between_abortion_or_adoption

lol...took me a sec to know who 'billy' was... whoa, wassup, billy-to-the G-dog.....

Spews coffee on computer.......

That teaching on adoption is so astonishingly evil and anti-Christian, it is amazing to me that Christian parents with any kind of discernment could buy into it. But maybe some families saw it as an easy way out with children who were giving them difficulties.

Sharon,

I agree.

All of the Christian families that I know are very supportive of adoption. Even those who followed Gothard that I know, did not buy into his adoption position, so I know that all did not buy into it and I also know that many were unaware of his views in this area. But, as we have observed, there are clearly those who believed that anything taught by Gothard must be truth and this is where insane things can happen. Also, what gets me is that, okay, fine, you don't agree with him on adoption, you don't agree with him on everything; after all, who agrees with another person on everything? But,look at what he is saying about adoption? I find it so evil and it has a real consequence that is tragic and destroys lives and hope. Why would anyone want to follow a man that holds these views? They are so against everything that Jesus stood for. If a person didn't know, that is one thing but once they know because you have shown them.... now what?

that plumbing picture that shows the holding back as an outlet for creativity... I think Draino would work better for those (ahem) clogged pipes.

Hahaha! Yes!

I showed my husband that picture of the clogged pipes and we decided it really was vulgar. Something about it just didn't set well with me. The Draino is a good idea for most of the billy's "insights".

Susanna,

Thank you for this great contribution to RG. You express your points very well.

The parallels are truly eerie.

A great article and well-written, Susanna. I would recommend "A Handmaid's Tale" by Margaret Atwood, if you haven't already read it. In a nutshell, it is about the control of women in a fictitious religious organization.

Susanna,

Thank you for your gracious attitude toward your parents. We, also, feel like completely duped failures, having fallen into the IBLP/ATI trap and now are at the point of needing to apologize and try to explain that we were also brain washed. I have read most of RG trying to understand how sincere parents who wanted children who are mighty in spirit have ended up in such a shambles. Many families are broken and children are hurting and unable to reconcile with parents. I am praying for the right attitude/words/timing for my apology to my grown children. It is truly devastating to realize that the most important role has been an utter failure. I am looking to God to help me heal and trust again. Thank you for this excellent perspective, which included forgiving your parents.

Dee, thanks for your willingness to acknowledge painful truths to your children! You mention something about being "an utter failure," but I'd just like to encourage you not to be too harsh with yourself. When we've been caught in performance oriented systems, we tend to view things as all good or all bad. In my own relationship with my parent, I can see it is very hard for her to acknowledge that certain things in my upbringing brought me pain. I think this is because she feels like if she messed up in any significant way, then she was a bad mother, and is a bad person. That, of course, is not true.

Dee May

A lot of us will be praying for you,,,

Dee, you and your family will be in my thoughts and prayers today.

Dee, if you are sincere, this attitude is all that most of us ever wanted from our parents. We know that no parent is perfect. We know they all make mistakes. It may take awhile for your children to believe your sincerity, so be patient. But for most of us, a sincere acknowledgement of the damages, was all we ever wanted from our parents. Good luck and God bless...

This is a brilliant comparison! Several years ago an online friend wrote an essay comparing the ATI experience to totalitarianism and while I saw some parallels I did not at that time understand the level of mind control as I do now. Thank you for sharing this, and keep on writing!

L,

Your kinds words of grace to Dee were beautiful, so appropriate on this website that is drawing us back to grace. I resonate with your statement that one impediment to reconciliation is your mother's "feel[ing] like she messed up in any significant way," which leads to thinking "she was a bad mother, and is a bad person." She believes, as you said a legalist is prone to, that parenting "is all good or all bad." I have seen this in others in her shoes. May the Lord minister grace to her hurting heart and the heavy sense of shame and failure that she carries for believing the lies.

We must acknowledge that false teaching is not merely man's error. It is Satanically powerful; "if it were possible" it would "lead even the elect astray," Jesus said (Mark 13:22). The apostle Paul, after laboring for 2 years in Ephesus teaching them "the whole purpose of God," warned that after his departure "savage wolves will come in among you, not sparing the flock," and that from among their own congregation "men will arise speaking perverse things to draw away the disciples after them" (Acts 20)! Deception is diabolically deceptive. Satanic doctrine sounds like it comes from "angels of light." When any one of us, led by the Spirit of Christ, finally sees the light of Truth in His Word, we must fall on our faces before Him with grateful hearts, not shameful hearts, and lay all our sins, our "mistakes," at the cross, then allow Him to bathe us in His forgiveness and grace. I'm praying your mother can come to this. When she recieves forgiveness from the Lord, she will be able to forgive and be forgiven by you (and others).

Hmmm, didn't realize we all were related and all came from the May family.:) Ha Ha!

Susanna wrote: 'I learned quickly to judge whether or not I could safely make eye contact with someone based on how they looked, dressed, or acted. At ATI gatherings, I was extremely guarded. How could I, in good conscience, make any friendship with anyone who dared to wear a skirt with flowers on it? How could I associate with another girl who was wearing sneakers—or worse, open-toed sandals?! How could I talk to someone who talked to boys and not be implicated right alongside her for being a flirt or a rebel—or more unthinkably, talk to a boy myself? It was impossible, so I kept my ministry smile on and hardly opened my mouth except to utter approved Institute phrases.'

it is stunning the level of insanity that Bill & Co. managed to pass off to us as normal. In winter 1994 I was with ATIA on a boat in the Moscow river. In the afternoons we visited schools, which I loved. In the mornings we studied. I remember one assignment was to go and find evidence that great men (not women, of course) followed the aphorism 'early to bed, early to rise makes a man healthy wealthy and wise. My study partner and I looked at the evidence available to us in the little library and our memories and concluded that there was no such evidence. But we didn't dare report that because it was not the approved conclusion. (Related: have you seen the diagram in Character Sketches that proved the scientific method is evil?)

Another time, we were watching a rather good video series about counselling and helping people to make change. The speaker used an example of a little child spilling milk because they filled the glass to full to show a non-blaming way of helping the child see their mistake and change. A Mr Oles stood up and ranted about how this approach was evil and George Mattix chimed, and that was the end of that video series. You can't go helping people to change without heaping a load of guilt on them, you know. Especially little kids. Kids need guilt.

When I was at ITC for a counselling seminar, this happened: https://www.flickr.com/photos/jqgill/4339864007/in/set-72157622749314542

And the adoption thing Kevin wrote about above. A family got rid of their child and suddenly had more money. Because money is way more important than people, especially your own children. (I'm a a biological and adoptive parent, so don't try to tell me a adopted child isn't my own or I will struggle to maintain a polite demeanour.)

Bill made insanity normal. Thanks for pointing it out well, Susanna.

Read your blog post, Jeff, that is hysterical.

It was such a funny moment, Sharon. I had no idea what everyone was staring at!

that is a funny story, but does it not demonstrate the power of music?

Grateful, yes, it does. Maybe that's why BG was so against people listening to most music? It can reach places his lists and manipulations could never get to.

Maybe someone can help me out I only went to one seminar in 88. Years later I bought the medical books that he had. There was one section on adoption and I thought maybe I was reading it incorrectly, but it seemed to me he was anti adoption. Now I see that others are saying the same thing and that there was actually teachings on it in an adoption booklet. I was wondering if it was the same one in his medical books. ( by the way I got rid of everything Gothard). I know he cited generational sins as one reason but what was his other reasons? And people actually sent their kids back because he said to??? Even if there was no problem with them? (I'm not suggesting it would be ok I'm just wondering even if the relationships were great if kids were sent back solely because gothard said to)

Yes, there was a booklet from the CARE program, these were basically booklets with dubious medical advice in them, and one was about adoption. It contained many cautions against adoption, one of which was sins of the birth fathers that would be passed onto the children. For example, one child was autistic because his mother was Native American and his father had left him. Of course I am being a bit tongue-in-cheek, but those who remember the story can attest that I have exaggerated only an iota, here.

Yes those are the books I had and every time I read them I felt a very oppressive spirit about them. I threw them out

Renea, This article covers more of the sources and what Bill said about adoption: https://www.recoveringgrace.org/2011/10/adoption-the-ultimate-act-of-grace/

That's a great article

Hi Renea,

The booklet that you may have read or are referring to is "Basic Care Booklet 5, How to Make Wise Decisions on Adoption"

Per your question:

" I know he cited generational sins as one reason but what was his other reasons? "

You mention the generational sin, and that is a big issue that the book spends a considerable amount of time dealing with, along with giving anecdotal examples of where this ostensibly has occurred. It offers very specific, seemingly magical, prayers to deal with removing these generational sins from a child's life- the famous "hedge of protection" prayer once again resurfaces.

Also, he warns about choosing to adopt because a couple is unable to conceive. The big concern, evidently, is that sometimes, after an adoption has occurred, the couple later conceive despite the fact that doctors have told them that it is impossible. In his mind this creates an unfortunate circumstance, as he warns " Are you prepared for tensions which may come from conception after adoption?" His biblical example is Ishmael and Isaac, citing tension between them, and noting that Ishmael had mocked Isaac.

He advises that rather than trying to satisfy what he calls the "craving of a barren womb" by adopting, that women should totally surrender to the Lord and rest in " His supernatural ability to open her womb".

In the case study that follows, he gives the story of a couple that were informed by their doctor that they were unable to conceive. While in the process of adoption, they attended a Basic Seminar and become convicted that they should trust the Lord and that " if God wanted us to have a child, then we should wait upon 'Isaac' and not rush to 'Ishmael' "

The couple rejected the referral of the three week old baby that was to be placed with them, following their new conviction. Several years later, they conceived naturally. As always, we see the case study 'proving' that those who follow the principles, in this case what is referred to as the "Death of a Vision principle", are rewarded by God and live happily ever after.

Adoption is described elsewhere as "taking matters into your own hands", as opposed to trusting in the Lord, regardless of whether the choice to adopt is due to infertility or for other reasons. I find his characterization offensive to adoptive parents. He totally ignores the possibility that some might actually be called by God to adopt. Also, characterizing it as: "wait upon'Isaac' and not rush to 'Ishmael' " is transparently discriminatory against adopted children, suggesting that adoptive parents have somehow settled for less than God's best, rushing into a poor decision.

He also claims, absurdly, that adoption causes abortion. As he often does, he cites some obscure study, without any specifics, so that one can look up the study, to support this hypothesis. Apparently, in this study, 150 unwed mothers were asked if they could not keep their child, would they "Surrender their child to adoption" or if they would have an abortion. First, I find the word choice of "Surrender" interesting. Interesting that an objective study, if it really exists, would use that word with the negative image it evokes. The results: 85 % of them chose abortion.

Supposedly , the reason given was that abortion had a finality to it, whereas adoption had a "continual anguish, similar to a son's being missing in action, which left the mother always wondering about the child's whereabouts."

An unnamed study, with twisted logic of the data, used to support the conclusion that adoption has "unwittingly been responsible for bringing about millions of abortions."

I don't believe in generational curses, but let's take those who do as an example. How SMALL is the God that they serve, if they think he is unable to remove a curse from their children?! He has already removed the curse of sin and death from our lives, so why wouldn't be be able to remove some kind of lesser curse caused by our father's sin? It's ridiculous. Everything these people do is based around fear.

I'm also wondering how adoptive parents can just send their kids back to the orphanage, as if they're returning an unwanted or defective item to Wal-Mart. If they are the legal parents of that child, wouldn't it be child abandonment? I mean, we can't just drop our biological children off somewhere; why is it different with adoptive children?

I would guess the reason some chose to send children back might be from fear. When your god is punitive, harsh and demanding, you fear consequences as prescribed by his representative. You want blessings and guarantees. We had a former elder in our church whose son spent a year in ATI whose family is in shambles. This man divorced his wife of over 20 yrs saying that his children are rebellious because he married her without his parents blessings putting her away as the Israelites were commanded of their foreign wives. He was connected at the hip to IBLP (this has transpired in the past 5 yrs).

It violates so much Scripture (we know that), but they were following a man ( victimized themselves). Pray for them; the stunning, awful realization of what they did is and/or will be something horrible to face and deal with when they come to their senses.

I know the things that God has shown me about my awful , ugly sin have been hard to face from so many angles. Not the least of which was the harm I inflicted on my children in the name of holiness, obedience and purity.

For quite some time I was worshipping a god of my own imagination.

His Grace is sufficient, His mercy is incomprehensible ...

Dreamer,

I happen to believe in generational curses.

I also believe it is incomprehensible to "send back" an adopted child.

We should all remember to thank God daily for adoption without which none of us would ever stand a chance over death.

Interestingly, the same ministry that taught me about generational curses also taught me the following, which now might be subject to verification (have learned a lot about embellishing facts after reading the tornado story on RG, geez!). I was told and believe while a father can absolutely disown a natural born son, An adopted son can never legally be disowned. It is a lifelong commitment. I guess given the light of circumstances, one could renig on adoption, but that would be placing them back to the pre adoptive state. Disowning would essentially be declaring one fatherless, or without a family.

Regardless, adoption is a beautiful picture of the state in which we are made whole and part of God's family. This is especially true if it can not be undone. For a "ministry" to declare dangerous the physical equivalent of that which makes us spiritually free, is such a legalistic stretch and a shame. The thought of some spiritual ghoul suggesting that a family would be better of sending a LEGAL child back based on principle, is worthy of a first class @$$ whipping (please forgive me for judging).

I have read numerous articles on this site, and that is the most clear example of outright abuse (and there are several) to me. How could any reasonable person think that this is a sound decision much less sound doctrine? Did this happen often in these circles?

If "adoption is taking matters into your own hands", what about the Duggars going to a fertility specialist to try to have a 20th child?

It's not at all clear that the Duggars are trying for another child. The doctor they visited was a high-risk specialist, not a fertility doctor from what I understand. If they truly believe that all forms of birth control are wrong (which they state they believe), their options are actually pretty bad right now. As far as I can tell, even if they recognize that a pregnancy would be unsafe for Michelle, they are limited to charting her cycle (no idea how effective that would be in pre-menopause) or abstaining till the chance of pregnancy is zero. They have boxed themselves into a corner- very publicly asserting beliefs that are now possibly dangerous. It'll be interesting to see how they handle it.

What's so "bad" about abstaining if a wife would be endangered? Is sex about other-centered love or appetite? This post sounds very pragmatic about birth control for one who sees only small, slight errors in Gothard's teachings and great benefits in keeping the law. Are you familiar with the manner millions of Catholics deal with these issues in a very deeply committed, Gospel-centered and unselfish manner (that celebrates large families but does not make an idol out of "as many as possible")? Are the Duggars in a "box" or an easily anticipated testing of their love and patience? Would you call commitment a "box" if one's wife is in a coma?

Don, are you saying you see great benefit in the law (presumably of Moses)? Read Acts chapter 15. The law is described there are "a yoke that neither we (living Jews) nor our fathers have been able to bear".

[…] Chilling. “1984 and ATI” by Susanna Wesley at Recovering […]

I see that there is another commenter using my initials. The above remarks on the Duggars are my sole contribution to this site, sorry for the confusion :) Also, I did not intend to disparage or commend their personal beliefs, merely to point out that with their self-imposed limitations there are other reasons to assess the potential danger of future pregnancies, besides seeking as many pregnancies as possible. And that while many others have the opportunity to reconsider their personal beliefs as they grow and change, the Duggars are committed to the beliefs they've been selling in books, speaking engagements, interviews, etc. That's a lot of pressure.

Forgive my confusion of you with another Mj.

That was not my representation of myself but I was burdening the poster, Mj, whose FB page claims to stand against heresy of grace alone by faith alone. Nevertheless, I do affirm that the Law is Good, as Paul states in I Tim 1:6ff:

"6 Certain persons, by swerving from these, have wandered away into vain discussion, 7 desiring to be teachers of the law, without understanding either what they are saying or the things about which they make confident assertions.

8 Now we know that the law is good, if one uses it lawfully, 9 understanding this, that the law is not laid down for the just but for the lawless and disobedient, for the ungodly and sinners, for the unholy and profane, for those who strike their fathers and mothers, for murderers, 10 the sexually immoral, men who practice homosexuality, enslavers, liars, perjurers, and whatever else is contrary to sound doctrine, 11 in accordance with the gospel of the glory of the blessed God with which I have been entrusted."

What insight you show, Suzannah! This article is excellent and I hope will spare many families the miserable consequences of getting caught in such a web of deception disguised as ministry.