About the author

More posts by Moderator

As Easter approaches with its commercialization of eggs and bunnies, the irony of new life is not lost upon those whose thoughts turn towards the events of Holy Week. In the first century a new faith came on the scene of the pagan Greco Roman world that literally turned that culture on its head. Its practitioners came to believe that their Lord, an obscure peasant from Nazareth in Galilee, was in fact the creator of the universe who demonstrated that reality by His resurrection from the dead. From this they were able to encapsulate the essentials of their faith in a poetic creed that was easy to memorize in that mostly verbal storytelling era, and which we are fortunate to have a copy of today.

As Easter approaches with its commercialization of eggs and bunnies, the irony of new life is not lost upon those whose thoughts turn towards the events of Holy Week. In the first century a new faith came on the scene of the pagan Greco Roman world that literally turned that culture on its head. Its practitioners came to believe that their Lord, an obscure peasant from Nazareth in Galilee, was in fact the creator of the universe who demonstrated that reality by His resurrection from the dead. From this they were able to encapsulate the essentials of their faith in a poetic creed that was easy to memorize in that mostly verbal storytelling era, and which we are fortunate to have a copy of today.

As a result of the arrangement of the gospels as the first books in the New Testament, we think of them as the earliest writings about the resurrection. In reality, though early, they are not the earliest writings about the resurrection. That distinction belongs to Paul the writer of so much of the New Testament, in his letter to the Christians in the city of Corinth. The evidence behind this being the earliest record is quite compelling. Readers of the book of Acts are aware of the legal incident involving Paul in Corinth when Gallio was the proconsul there. [1] What is significant about this seemingly inconsequential tidbit recorded by Luke is an archeological find at Delphi. There in the ancient Grecian city is an inscription by the Emperor Claudius that mentions Gallio as holding the office of proconsul in Achaia during the emperor’s twenty-sixth acclamation as imperator. That period has been determined to cover the first seven months of A.D.52 [2] Depending on the timing of the event recorded in Acts 18 (i.e.: whether Paul’s difficulties occurred early or late in Gallio’s term of service), Paul’s writing of 1 Corinthians occurred a relatively short time after completing his ministry there which was somewhere in the mid-fifties. [3] Thus the information from 1 Corinthians is approximately twenty-five years after the resurrection itself, a very short time in terms of ancient literary records of historical events.

However, the evidence within the text itself indicates that Paul is actually conveying even earlier material and this is where it becomes very interesting. Paul essentially uses rabbinical terminology when he writes to the Corinthians, “For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received …” The meaning is basically that in this section of the letter he is not writing new material, but rather recording the tradition (probably oral) that he had received from others. “These two texts together make it clear that this is technical vocabulary from Paul’s Jewish heritage for the transmission of religious instruction. As with the tradition of the Lord’s Supper, this language indicates that the essential matters go back to the very beginnings of things … [and] were well formed before Paul come on the scene.” [4] Those from whom Paul received the tradition would have been the founding apostles, most likely Peter and James. The reason Paul wants to convey this as common tradition is because he wants the reader to understand that the gospel is consistent across the early church. He noted in verse eleven, ‘Whether then it was I or they, so we preach and so you believed.” Thus the creedal discussion in 1 Corinthians 15 is an extremely early record of the worship of the early church. Some have estimated its composition as early as six months, certainly no later than a few years after the resurrection. It’s like having in your hands an example of the liturgy of those ancient Christian communities gathering on the first day of each week. [5] With this knowledge, let us take a fresh look at what is the very earliest text about the resurrection which is not only powerful in its scope, but also rhythmic in its presentation.

However, the evidence within the text itself indicates that Paul is actually conveying even earlier material and this is where it becomes very interesting. Paul essentially uses rabbinical terminology when he writes to the Corinthians, “For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received …” The meaning is basically that in this section of the letter he is not writing new material, but rather recording the tradition (probably oral) that he had received from others. “These two texts together make it clear that this is technical vocabulary from Paul’s Jewish heritage for the transmission of religious instruction. As with the tradition of the Lord’s Supper, this language indicates that the essential matters go back to the very beginnings of things … [and] were well formed before Paul come on the scene.” [4] Those from whom Paul received the tradition would have been the founding apostles, most likely Peter and James. The reason Paul wants to convey this as common tradition is because he wants the reader to understand that the gospel is consistent across the early church. He noted in verse eleven, ‘Whether then it was I or they, so we preach and so you believed.” Thus the creedal discussion in 1 Corinthians 15 is an extremely early record of the worship of the early church. Some have estimated its composition as early as six months, certainly no later than a few years after the resurrection. It’s like having in your hands an example of the liturgy of those ancient Christian communities gathering on the first day of each week. [5] With this knowledge, let us take a fresh look at what is the very earliest text about the resurrection which is not only powerful in its scope, but also rhythmic in its presentation.

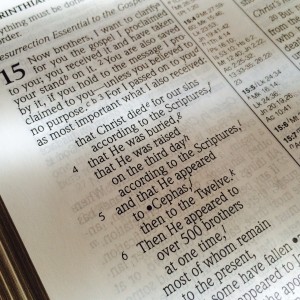

Take a moment and read 1 Cor. 15.1-19. As you read notice that in the first segment Paul is telling the Corinthian’s that he is repeating what they should already know. It will be the basis of his argument concerning the resurrection. He also wants them to be clear that the resurrection (the main topic of the chapter), is of “first importance,” that is to say it matters the most of all. As his argument progresses we readers are led to understand that the resurrection is the center of the faith, not some optional add on. He begins his quote of the creed in the second part of verse 3 which can be seen in the rhythmic layout below:

and that he was buried; and that he appeared to Cephas, then he appeared to James,

According to the Scriptures;

and that he was raised on the third day,

According to the scriptures;

then to the twelve.

after that he appeared to more than five hundred brethren at one time,

Most of whom remain until now, but some have fallen asleep;

then to all the apostles;

Some would break off the creed at “…then to the twelve,” but as you can see the poetic rhythm is quite obvious, even in the English translation. Each of the “that” words introduce a new line of the creed. So often, because we have the scriptures available in book format, we forget the early church was an oral culture. They did not go around with “bibles” to “church”. An oral culture uses structures such as we see above to remember the essential truths both for instruction as well as passing on. So this resurrection weekend as we press our minds back to the earliest members of our faith what should we focus on? There are at least four truths that we not only pin our eternal hopes on, but which we also should come to understand as worth giving our lives for.

God in his life he explains why it is so important. No resurrection means Jesus was not resurrected. No resurrection means no salvation, no forgiveness of sins, no hope, and that life really is in vain. No resurrection means Christianity is a lie and those who teach it are liars. It is not a pretty picture. That is why Paul is so adamant in his message that the resurrection, which is based on historical evidence, and the church has now expounded for centuries, is so paramount.

God in his life he explains why it is so important. No resurrection means Jesus was not resurrected. No resurrection means no salvation, no forgiveness of sins, no hope, and that life really is in vain. No resurrection means Christianity is a lie and those who teach it are liars. It is not a pretty picture. That is why Paul is so adamant in his message that the resurrection, which is based on historical evidence, and the church has now expounded for centuries, is so paramount.So this Good Friday as you contemplate the death of Jesus allow the seriousness of his death drive deep into your soul. Don’t mitigate the implications of our sin being the real force behind the scourging and the nails and the spear. But never forget that Sunday is coming! And when you rise up from your bed Easter morning remember the one who rose up from the grave. It truly is a wonderfully amazing, full of grace gift of new life.

Photo of tomb © / 123RF Stock Photo

Footnotes:

[1] Acts 18

[2] Carson, D. A., Douglas J. Moo and Leon Morris. An Introduction to the New Testament. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Publishing House, 1992. 282.

[3] Morris, Leon. Tyndale New Testament Commentaries; Volume 7: 1 Corinthians. Downers Grove, Illinois: Inter-Varsity Press, 1985. 35.

[4] Fee, Gordon D. The New International Commentary on the New Testament: The First Epistle to the Corinthians. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1987. 722-3.

[5] 1 Corinthians 16:1

[6] Fee, 726.

[7] John 20.8

[8] Acts 4

Wonderful truths to ponder today. Thank you. May the truths of Easter live in our hearts and be manifest in our lives every day.

Really appreciated reading this reflection today.

Great post (and I hadn't even read it yet, when I suggested on other threads that the early Creeds give a reliable framework for understanding the gospel and interpreting the Scriptures).

From an Orthodox perspective, I would qualify one thing, though. That "Christ died for our sins" is without a doubt foundational to the gospel for any who would claim to be "orthodox" Christians. On the other hand, that the meaning of this statement from the Scriptures is properly explained by the Penal Substitutionary Atonement theory of the Protestant Reformers (and many modern Evangelical explanations of the same) is a completely different question, however. An Orthodox Christian (and an increasing number of Evangelicals who are becoming more conversant with the world and thought of the early Church Fathers) would have to resolutely dispute that notion and at least seriously qualify that theory's assertions (or popular modern presentations of it) on several points.

I will just quote one aspect of what Christ's substitutionary death on our behalf does not imply from the perspective of one of the greatest theological thinkers in the early Church (who read the Scriptures in the original Greek). St. Gregory the Theologian, one of the formulators of the Nicene Creed, writes in his Second Paschal Oration (i.e., fittingly, in an Easter sermon) in response to some theories of the Atonement being offered in his day on the question of to whom the "ransom" of Christ's death was paid:

"Now we are to examine another fact and dogma, neglected by most people, but in my judgment well worth enquiring into. To Whom was that Blood offered that was shed for us, and why was it shed? I mean the precious and famous Blood of our God and Highpriest and Sacrifice. We were detained in bondage by the Evil One, sold under sin, and receiving pleasure in exchange for wickedness. Now, since a ransom belongs only to him who holds in bondage, I ask to whom was this offered, and for what cause? If to the Evil One, fie upon the outrage! If the robber receives ransom, not only from God, but a ransom which consists of God Himself, and has such an illustrious payment for his tyranny, a payment for whose sake it would have been right for him to have left us alone altogether. But if to the Father, I ask first, how? For it was not by Him that we were being oppressed; and next, On what principle did the Blood of His Only begotten Son delight the Father, Who would not receive even Isaac, when he was being offered by his Father, but changed the sacrifice, putting a ram in the place of the human victim? Is it not evident that the Father accepts Him, but neither asked for Him nor demanded Him; but on account of the Incarnation, and because Humanity must be sanctified by the Humanity of God, that He might deliver us Himself, and overcome the tyrant, and draw us to Himself by the mediation of His Son, Who also arranged this to the honour of the Father, Whom it is manifest that He obeys in all things? So much we have said of Christ; the greater part of what we might say shall be reverenced with silence."

The early Church Fathers concluded that an early theory of the Atonement, the "Ransom Theory", erred in suggesting the ransom of Christ's death was paid to anybody--and especially in suggesting it was paid to that usurper, the devil! Rather, they concluded this Scriptural language is simply present to affirm that Christ's death (and resurrection) are what effectively free us from our bondage to sin and death. Both the Scripture and the early Creeds stop short of explaining exactly how it is this works, which is why St. Gregory suggests reverent "silence" is to be preferred to the speculations of the Ransom theorists of his day. I'm quite certain he would say the same of Anselm's "Satisfaction" theory and the Reformer's "Penal Substitution" theory, which are more modern attempts at explaining this foundational dogma of the gospel, but both of which also go beyond the actual texts of the Scriptures and introduce anachronistic and alien frameworks back into the Scriptures' teaching (i.e., the notion of "feudal honor" for Anselm and Enlightenment notions of criminal law for the Reformers). In so doing, many have argued the language frequently used in explaining these theories distorts our understanding of the nature of God, the Father, in His motivation and role in the death of His Son. I agree with those who so argue.

Karen

I realize this is a few years old, but I felt it deserved a reply for future readers of the original post & the replies.

Though I am certainly familiar with the various explanations I did not reference or specifically state any of them.

The Socinian Theory of atonement as an example

The Moral-Influences Theory of atonement as a demonstration of God’s love

The Governmental Theory of atonement as a demonstration of Divine justice

The Ransom Theory of atonement as Victory over the forces of sin and evil

The Satisfaction theory of atonement as compensation to the Father

The Penal-Substitution theory of atonement

Rather I simply reflected back the text. Any perspective that does not regard Jesus dying on our behalf clearly cannot be considered Orthodox as you acknowledge. So using the general understanding of “Christ Died for Our Sins” in the creed, I merely stated that Jesus died in our place - he was a substitute, he received the penalty for our sin. If in fact the creed and Paul did not think that to be the case, it is hard to square with his reflections in other places such as Colossians 2. 13-15

When you were dead in your transgressions and the uncircumcision of your flesh, He made you alive together with Him, having forgiven us all our transgressions, having canceled out the certificate of debt consisting of decrees against us, which was hostile to us; and He has taken it out of the way, having nailed it to the cross. When He had disarmed the rulers and authorities, He made a public display of them, having triumphed over them through Him.

Here it would seem to me that Paul is clearly picturing our debt of sin being nailed to the Cross in Christ. How you cash that out can be varied perhaps though I find some of the ideas (such as the Socinian and Moral-influence) simply inadequate. It is also much harder to align with the entire OT sacrificial system where the entire picture is one of some form of substitution. Granted as the writer of Hebrews acknowledges, that system was ineffective, but that was his point! Jesus death WAS effective. His sacrifice was efficacious (Heb. 10).

Further while there is no question of God, our loving Father, reaching down to us versus us reaching to God, It is the supreme example of God’s love that Jesus took on our sin as the sacrificial lamb of God (John 1.29 ff), however that was considered by God to be the case. As Erickson noted in defending Penal Substitution (though these do not apply only to that view):

God would not have gone so far as to put his precious Son to death had it not been absolutely necessary. Humans are totally unable to meet their own need … [In addition] God’s nature is not one sided, nor is there any tension between its different aspects. He is not merely righteous and demanding, nor merely loving and giving. He is righteous, so much so that sacrifice for sin had to be provided. He is loving, so much that he provided that sacrifice himself. [1]

While the explanation of how the sacrifice ‘works’ can be explained in different ways or even left ‘silent’ anything short of Jesus dying in our place because of our sins simply does not do justice to the Passion of the Christ.

[1] Millard J. Erickson, Christian Theology (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books, 1998), 840.

Thanks, Karen. Your explanation was more clear than Gregory's in that translation ("fie" indeed!).Very provocative.

Our instruction in the Torah and the Book of Hebrews add to the mystery: Heb. 9:11-14, 23-26. That verse 23 indicates that eternal, heavenly things are "purified" by His blood. Could we possibly comprehend such?

I wonder how much our ignorance of covenant impacts our inadequate "payment of debt" perspective. The easy transition in Paul's writing from "covenant" to "testator" may be a key: What I receive through a will is pure, undeserved, bequest, "purchased" (only by analogy) by the blood or death of the testator who made the bequest. It is nothing, only words, not even promise, so long as the testator lives. (You can change your will any time you wish.) It becomes unchangeable law when the testator dies.

What wondrous Love is this. Not a ransom paid to another, but a ransom's price given FOR my inclusion in an eternal communion. Priceless bequest.

I like your observations, Don. It's very true that how well we understand the nature of an OT covenant impacts our understanding of the nature of the New Covenant in Christ's Blood. We, all too easily, it seems conflate ideas of legal contract with testament, the nature of which you have described well. (Your lawyerly training is serving us well here! :-) I believe you are a lawyer, no?)

Penal substitution language tends to imply or even explicitly teach that the price Christ paid was what was owed by sinful humanity to God (or to God's "justice"). God is conceived of in this scenario as as sort of "Grand Creditor in the Sky," but Scripture never teaches that God is our Creditor, but rather that He is our loving Father, who scans the horizon looking for the return of his prodigal children. Indeed, He is the Good Shepherd who leaves the 99 that are in the fold to look for the one who is still lost. The Nicene Creed states simply that Christ became incarnate as a man "for us men and for our salvation," not because God was demanding a retributive price to be paid to meet the demands of His "justice" (in the "eye for eye, tooth for tooth" sense).