Since our readership has rapidly expanded over the past few years, and especially during the past few months, we want to take some time this summer to draw attention to earlier articles for those who may have missed them. Today's article was one from early last year, yet its clarity in discussing the issues found in the Wisdom Booklets lends it to be an excellent post for re-issue .

Sometime last year I told my wife that the pastoral staff of our church were preparing a series on the Sermon on the Mount. Having not grown up in the ATI world (in the Advanced Training Institute), I had not anticipated her less-than-enthusiastic response: “Yeah, I’ve had enough teaching on THAT to last me my whole life.” And it’s true. If you are ex-ATI like my wife, it’s likely that you were educated in part through Bill Gothard’s 54-module “Wisdom Books,” which uses these three chapters of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount teaching as a framework for an entire homeschool curriculum.

Sometime last year I told my wife that the pastoral staff of our church were preparing a series on the Sermon on the Mount. Having not grown up in the ATI world (in the Advanced Training Institute), I had not anticipated her less-than-enthusiastic response: “Yeah, I’ve had enough teaching on THAT to last me my whole life.” And it’s true. If you are ex-ATI like my wife, it’s likely that you were educated in part through Bill Gothard’s 54-module “Wisdom Books,” which uses these three chapters of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount teaching as a framework for an entire homeschool curriculum.

If you’re reading this, you’re probably familiar with the Wisdom Books, but in case you’re not, let me illustrate. Did you know that you can take one verse from the Sermon on the Mount and use it to teach not only Bible, but also science, history, social skills, ethics… everything? Take Module 15, for instance: “Ye are the light of the world.” These words of Christ become a launch point for discussions on the Church as a light during the Crusades, the science of the eyeball, the medicinal value of sunlight, biblical citations for each color of the prism, and my personal favorite… found on page 621:

“Learn ten ways to direct the eyes of others to your countenance.”

“Learn ten ways to direct the eyes of others to your countenance.”

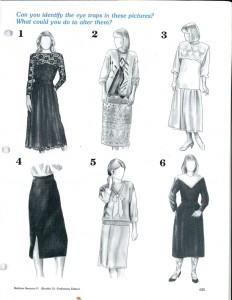

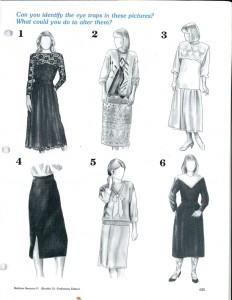

In other words, if you’re going to be a light, how do you get other people to notice it? There are several suggested tips, including incessant smiling, choosing colors which enhance your skin tones, and avoiding “eye traps.” An eye trap is something that draws attention to a place of the body it shouldn’t be drawing attention to (thereby dimming your light). An accompanying quiz asks, “Are you able to identify the eye traps in these pictures?” As an outsider to the Wisdom Books, I must admit that all six of the women pictured here look decidedly Puritanical to me, but my wife has been well-trained and can identify all six. Can you?

But the bigger question is this: Is this really what the Sermon on the Mount is about? No doubt there is some wisdom in the Wisdom Books, and it took great creativity and effort to frame the different subjects and academic disciplines—from math to history to civics—around Jesus’ famous sermon. If you’re an alumnus of the curriculum, I suspect you learned some helpful things and are likely to remember some positive stories, activities, and illustrations.

But the overall effect is concerning, because of what becomes of the actual Sermon on the Mount. When we force these verses to say things well beyond their original intention, we lose the powerful essence of the sermon’s original meaning. Imagine bringing home an elaborate vintage oil painting, hanging it on your office wall, and then using it as a bulletin board for your various post-it notes, photos, and to-do lists. The pushpins may hold, but the add-ons will quickly obscure the intended beauty underneath.

In the case of the first verses of the Sermon on the Mount, commonly called the Beatitudes, this message is crucial. By using these verses in booklets 3 through 12 to portray character qualities to pursue and principles to master, the Wisdom Books examine the post-its at the expense of the canvas, and all the extras leave us with something less than the words of Christ. As much as the subject matter may be interesting or even necessary for a student to learn, Jesus didn’t bless the meek so we could understand gastric ulcers[1] or bless the mourning so we could use pi to calculate the circumference of Ninevah.[2]

Although a more novel approach, Gothard isn’t the only person to present the Beatitudes (Matthew 5:1-12) as a list of characteristics to pursue, a sort of “Eight Commandments for the New Kingdom.”[3] But consider this. If this is simply a presentation of the new Christian morality—the priority qualities of the ‘new regime’—then in the Beatitudes we essentially have an eight-step process on how to engineer your way into the Kingdom. Just be humble, and you’ll be blessed. Just be a peacemaker, and you’ll be blessed. I appreciate Dallas Willard’s words that this approach creates “If not salvation by works, then possibly salvation by attitude.”[4] I’ll be blessed if I can gain the right attitude or—better yet—contrive the right circumstances of sadness[5] or insult[6] or persecution.[7] The usually-unintended result paints Jesus’ words as a place of guilt, a place of excessive law, a place of higher standards and measuring up, not a place of good news, and the message that no one is beyond beatitude.

Stripping away the clutter of post-its for a moment, consider the canvas. If you’re reading this article, it’s probable that you, like my wife, have lost the luster of these verses amongst the educational accoutrements of the Wisdom Books. Perhaps your exposure to the Beatitudes began with that unfortunate parking lot people-judging assignment[8] and ended with a map of U.S. pollen concentrations.[9]

But what if the Beatitudes are far more straightforward than that? In fact, what if they aren’t about the earning of God’s favor at all? When Jesus spoke to this original audience on the mountain, he wasn’t creating a new religious manifesto for them—or us—to attain to. He wasn’t telling them—or us—how to earn points with God. Instead, what if Jesus is saying that in all these places and more—meekness, mourning, persecution, and all the rest—through him we can experience the Kingdom? It’s essential to grasp the gospel message that if a person is in Christ, they already have his favor and blessing. The blessing does not need to be elicited or engineered by maintaining the proper attitudes or circumstances. And if this is true, then the Beatitudes must not be about the earning of God’s favor, but about the experience of his Kingdom. Jesus is explaining the places where we can enjoy and experience the blessings of the Kingdom that are already ours in Christ.

Far from being a place of jaded do-goodism, the original audience of Jesus’ words would have been floored by this. Jesus is speaking on the fringe of Israel to the fringes of Judaism and the very people who would have been defined by the society as the not-blessed. Matthew 4:24 describes the very audience of this sermon as “all who were ill with various diseases, those suffering with severe pain, the demon-possessed, those having seizures, and the paralyzed.” These were people who knew instinctively to step out of the way when a good Jew came down the street, who knew not to make eye contact because of their condition or their disease, who didn’t hold the positions of power or the successful jobs.

From this milieu came a crowd of disciples; they were healed, gathered, and taught. If the Beatitudes don’t make sense to us, perhaps we need to scoot up into the crowd alongside these folks and listen to Jesus’ words like they would have heard them. “Jesus is saying we’re blessed! We who would never be ritually clean, we who wouldn’t be admitted to the temple, we who have had to go through the streets yelling ‘Unclean! Unclean!’—this new Rabbi is saying that we can experience the Kingdom. That we can be called blessed. That no one is beyond beatitude!” Jesus turned the culture’s kingdom-conceptions upside down with these words. In a culture (not unlike ours) where religious people assumed that virtuous lives would be marked by exterior successes, Jesus encouraged a mountainside full of have-nots with a radically different definition of blessedness: There’s hope for everyone! The Gospel of Christ provides a way for outsiders to be redefined as insiders.

Sadly we have dissected the message to death. It’s easier to indict the Wisdom Books because they did it with greater magnitude, but we are all prone to add to the message, to miss the exuberance of the amazing message of a “gospel for misfits.”

Yes, the Beatitudes are qualities we’re called to pursue. Both the Old and New Testaments call us in many places to live meekly, to be peacemakers, to pursue a pureness of heart. But the beatitudinal nuance is this: I pursue these things not to secure the blessing of God, but to experience the nearness of the Kingdom. The more you pursue the Kingdom the more you’ll see these things in your life, and the more you see these things in your life, the more you’ll experience the Kingdom.

You may love the Wisdom Books and look upon them with great nostalgia. I’m simply trying to get past the curricular exercises to the awe and beauty of the message itself: If we are in Christ, we already have God’s blessing, his beatitude. We don’t want to miss the wonder of the canvas underneath. Jesus is sharing the great news of a Kingdom turned upside down, a new regime that makes a way for the have-nots to have it all. And in the Sermon on the Mount, that’s the greatest wisdom.

[1] Wisdom Booklet 5, p. 153: “How is our health affected by not yielding our personal rights?”

[2] Wisdom Booklet 4, p. 131-132. The linear progression of thought here is that mourning means repentance, that repentance often utilized sackcloth, as demonstrated in Jonah 3—and while we’re at it, let’s do some math!

[3] I take verse 11 as a thought connected with the ‘salt and light’ passage in vv. 13-16. However, if you prefer to treat it as the last beatitude instead, then there are nine, not eight.

[5] Matthew 5:4: “Blessed are those who mourn…”

[6] Matthew 5:11: “Blessed are you when people insult you…”

[7] Matthew 5:10: “Blessed are those who are persecuted because of righteousness…”

[8] Wisdom Booklet 1, p. 10, “How to Develop the Spiritual Skill of ‘Seeing’ People as Jesus Saw Them”

[9] Wisdom Booklet 11, p. 450.

Sometime last year I told my wife that the pastoral staff of our church were preparing a series on the Sermon on the Mount. Having not grown up in the ATI world (in the Advanced Training Institute), I had not anticipated her less-than-enthusiastic response: “Yeah, I’ve had enough teaching on THAT to last me my whole life.” And it’s true. If you are ex-ATI like my wife, it’s likely that you were educated in part through Bill Gothard’s 54-module “Wisdom Books,” which uses these three chapters of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount teaching as a framework for an entire homeschool curriculum.

Sometime last year I told my wife that the pastoral staff of our church were preparing a series on the Sermon on the Mount. Having not grown up in the ATI world (in the Advanced Training Institute), I had not anticipated her less-than-enthusiastic response: “Yeah, I’ve had enough teaching on THAT to last me my whole life.” And it’s true. If you are ex-ATI like my wife, it’s likely that you were educated in part through Bill Gothard’s 54-module “Wisdom Books,” which uses these three chapters of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount teaching as a framework for an entire homeschool curriculum.

I think one of the biggest issues plaguing today's Western church - and one of the biggest reasons why organizations like IBLP have been so attractive - is the embracing of modernist tendencies. The use of Scripture as a magic pill to answer every important question or to be applied to as many arenas of life as possible certainly fits right into the paradigm. This is very characteristic of the way most moderns view truth and knowledge: whereas premodernism (before the Renaissance, Reformation, etc.) was characterized by looking to the past and at multiple sources for truth (intuition, observation, divine revelation, tradition, etc.), modern handling of knowledge rejects the past and is very compartmentalized, with truth wrapped up in a single "silver bullet" designed to tell everyone all they need to know, at least practically, about life. Protestantism, which is arguably a modern expression of Christianity with its Sola Scriptura, chose the Bible as this one source of truth. Most secular moderns use Science as their "silver bullet." Whatever can't be known from these "silver bullets" is, for the moderns who choose these "silver bullets," not worth knowing. Now, we're entering an age of postmodernism that is the natural response to the insufficiency of silver bullet thinking. Only instead of returning to a more classical understanding of truth, our culture is taking modernism a step further by rejecting every truth source altogether and embracing nihilism and subjectivism.

What's really sad is that modernism is not only not a very comprehensive view of truth that ignores other legitimate means God uses to deliver it, it also has had an incredibly negative influence on how we treat each other as human beings. Modernism has taken what was generally assumed about the three human needs of culture, deep relational networks, and spiritual nourishment and relegated them to superstition. Positivist Scientism, the dominant secular version of Modernism in the West, says that humans are just animals and that animals are just machines. Because of this, humans are treated, and taught to treat themselves, as nothing more than machines without these three holistic needs. Emotions are stigmatized as inappropriate and irrelevant. Stories are de-emphasized. What's unfortunate is just how much these tendencies have pervaded the church - and this post-it note-esque handling of the Bible is just one piece of that puzzle. We treat spirituality and discipleship as essentially programming a computer as we put the silver bullet to work: "memorize this verse to counter this sin in your life." Sinners are faulty machines to be rejected and discarded rather than human beings with whom we have relationships who are in process and on a journey towards being more Christlike. Even when we do repentance, restoration, and reconciliation work, it is usually seen as a one-time act which changes everything and is now over, as if we replaced the belts on a car and it will now run the air conditioner or the alternator as well as it is supposed to without further attention. This sweep-under-the-rug handling of the scandals within IBLP is just one example among many.

you point out very well the over reach of Gothardism. It is amazing that a very simple verse about being the light of the world is twisted into an essay about women's fashion and bogus eye traps. You also point out very well the problem from your wife's statement about not really wanting to review the Beatitude because she heard it all before. I have found this to be true with some verses the WoF people used in their false teaching. It is sometimes hard to deprogram oneself from false or misuse of different Bible passages and what ends up is that one either doesn't read them or skip over them.

The first time I sat down to study Matthew post ATI was with my husband of about 4 years. I felt like a child, but in a good way. I was shy, nervous, and vulnerable, but anticipating getting a whole new, fresh look, and I did!

Okay, I'm going to try my IBLP eye trap identification skilz;

Dress 1: Got it. Eye trap could be avoided by adding ski jacket or shawl. He he.

Outfit 2: Ummm...so I'm guessing necklaces are an eye trap? Maybe for a raccoon. I've heard they lust after shiny things.

Outfit 3: Ummm. Now I'm completely lost. Poor thing looks pretty homely to me. Maybe she used too much makeup? :-)

Outfit 4: Definitely need some safety pins, girl.

Outfit 5: So, if she's an eye trap, it's not possible to avoid eye traps.I can admit that outfit 1 might be a little flashy for some occasions, but this one?

Outfit 6: Please tell me we're not going to tell this girl to be more modest. Poor thing just walked off the Mayflower. Don't even try to tell us it's her stocking. Most people, 'cough'don't struggle with feet.

Love your commentary, Daniel. :-) These ladies pictured have eye traps?? Like you, maybe # 1 - I think it would have been considered dressy in the 1940s or 50s - I think I remember movies from that era where the ladies were attired like that. When was the relevant Wisdom Booklet written - the 90s?? Was anyone in the "real world" wearing attire like this when the Wisdom Book was written???

A possible exception might be the skirt in # 4 - and how would the wearer walk if the skirt (must be modest - notice - no knees showing!!) was stitched shut for the full length?? Was ankle-length the only permissible length for skirts in IBLP? And they must be full, not straight skirts?

(I wasn't IBLP - I attended 2 Basic Seminars in college in 1973 and the anti-rock-music stance stuck with me for a few years as a bondage, but the rest of it bit the dust pretty quickly.)

The 'Post-it'-ing of the Sermon on the Mount as described here hides the simplicity of the words of Jesus. Because of it, many people - like your wife - have gotten seriously turned off and (probably) won't even look at it for the REAL truths in it. Thank you for this excellent article, especially for providing the context of the original hearers of it. Context of verses is so important.

ok let me take a crack at this.

1. lacy top that shows skin

2. drawing is hard for me to see but either it is the sweater being bunched up at least that what it looks like

3. the collar top cuts across the breast line and is too pronounced

4. slit in skirt

5. scarf tangles too low and the top's bottom is on the hips

6. the v neck

Now if one is being tempted by any of these out fits, they have the problem not these outfits. Maybe these outfits are tempting to BG, if so he really needs to get some serious help.

I didn't catch # 6 having a V neck - thought it was an over-collar (like a sailor suit collar, only a V shape). I like your comment: "Now if one is being tempted by any of these out fits, they have the problem not these outfits. Maybe these outfits are tempting to BG, if so he really needs to get some serious help."

ALL of those ladies are wearing what society would call modest or even prudish outfits, no eye traps...what I wonder is why BG chose these outfits to find something wrong with them and not use samples of models with very short skirts or pants, low waist pants with muffin top bulges, low cut tops with spaghetti straps...his type of theology has the viewer so deeply ingrained as to what a woman of God should dress like (more like burka and long shapeless robe) that the least bit of soft or sensuous fabric, a tiny bit of skin showing and the viewer goes into mind orgies. Of course, the woman is at fault. If BG wants to see some eye traps today all he has to do is go to Walmart.

Great comments, Esbee!

The man equated sensuality with lust. That alone explains many of his errors. Do you think Adam was not sensually motivated in Genesis 2 when Eve appears? He uttered the first poetry for goodness sake, and he spoke of {shush!} "FLESH".

yes, Adam was so pleased with Eve he said to God..." I got more ribs."

I think rob war is on to something here: these examples may be just the tip of the appropriate-to-publish-in-IBLP-materials iceberg with respect to Bill's personal fetishes.

Yes, esbee, the woman IS at fault. EVERY time, without fail. I really believe that there is an etiology of the basic problem in Gothardism that is very deep, very dark, and very suppressed.

If you go back and read his teaching on authority, his character sketches, and other writings, women are always at fault. For a great example, check “Lessons From Moral Failures in a Family” where almost everything boiled down to either what the mom was doing wrong, OR what she failed to do at all. Men are occasionally at fault, but almost always ONLY because they have "allowed" their wives or daughters to do things they shouldn't have allowed.

Bill consistently describes error differently by gender. For women, it's what they've done wrong, which is almost everything ... not dressing right, not performing child care or housekeeping adequately, not smiling enough, working outside the home, making their own decisions, having bad attitudes or bitterness, not getting up early enough or staying up late enough, etc. When he occasionally points out something about a man, what it usually boils down to is that he didn't properly exercise his authority over a woman.

So if everyone does what they're supposed to do, then women are suppressed and men will continue to suppress them, and if men aren't suppressing hard enough, they need to try harder. Everybody wins ... NOT! Only Bill wins.

Combine this deviation with some apparent sexual deviations ... young women/girls, a fixation on "purity" in himself and others, and even a foot fetish. Would make for pretty interesting psychoanalysis ... if IT wasn't discredited, of course!

I would love to have been a fly on the wall in his house and seen the family dynamics as he was growing up.....some of the things his sisters have said and done (in one story a woman recounts how overly reactive Bill's sister was to seeing her wear jeans) are a clue to the rest of the iceberg of what may be wrong in that family. I wonder if that family wasn't a matriarchy.

The jean thing?! You have got to be kidding, esbee. Let's go back . . . the entire staff is in an uproar, intrigue and groups and secret meetings. They call an emergency night meeting to deal with "rebellion". Back in the day women wearing pants was a big ministry deal. So . . . the wife of a senior staffer shows up . . . in pants. Now . . . HOW do you think the folks took that that were feeling like everybody was "in rebelion"? It would be taken as a deliberate statement, slight, insult . . . in THAT meeting under those circumstances.

Bill told me Anne winced when she read that account. But . . . it was too much for frayed nerves, I am guessing.

Alfred, according to Joy's testimony, she was at a park with her children and was called to this meeting as an emergency during the day, she didn't have time to stop back at the house and change. Considering the circustances that Steve was having immoral sex with a number of the females on staff and it was ignored by Bill for 5-6 years. the gross immorality is the bigger issue not whether some wife of a staff member showed up in pants or jeans to be yelled at by Bill and Steve's sister.

That reminded me of this:

"A modern illustration of straining at gnats and swallowing camels happened at a local (to one of our authors), conservative, fundamental church known for taking strong stands on issues. For instance, they took a strong stand on dress code in church; a communion steward would be prevented from serving communion if he failed to wear the required coat and tie. One day, a shocking revelation, followed by another and more after them: the pastor had been molesting children. It was dismaying to find that the church leadership was aware of a problem (though not the full extent) and had felt it best to sweep the problem under the rug and keep up appearances. Enforcing a coat-and-tie dress code while turning a blind eye to sexual abuse is straining at gnats and swallowing camels."

(https://www.recoveringgrace.org/2012/09/the-subtle-power-of-spiritual-abuse-chapter-12-straining-gnats-swallowing-camels/)

Alfred,

You once again belittle someone else's comment instead of dealing with the article. Kevin did an outstanding job of explaining the problem with Bill's teaching. Reinterpreting the sermon on the mount is like post it notes on a masterpiece. Do you get that? Do you care? When people read an article and respond, it is because they can relate in some way to what they have read. Esbee's comment was completely valid. Deal with it.

Two of our sons went to Indianapolis to that hotel place. They had to stay an extra day because of train schedules. They tell me that as soon as the 'training seminar' was over and they were the only ones left, all of Bill's young girl helpers changed into blue jeans. What's with that?

I have lived in closed fellowships all of my life, many of whom would drop dead if I wore jeans to any church meeting. Let alone women wearing pants of any kind. These are fellowships that, BTW, generally eschew Bill Gothard, so there is no influence there.

I can tell you beyond any shadow of any doubt, where there is a will, there most definitely is a way. When the stakes to the contrary are high, as where I go, no woman on earth will be caught dead in pants.

Given that they lived on campus, it really struck me as strange that it was simply not possible to change. Sorry . . . that part I don't buy. My opinion, for whatever it is worth.

"where I go, no woman on earth will be caught dead in pants"

The unfortunate reality for many women in places like that is that they will be attacked deeply and personally if they deviate from the rules about outward appearance (no pants, headcovering, whatever the rules happen to be). But those same women can be harshly treated, even used and abused, behind the scenes by men and the men will get a free pass. The women will be pressured to continue to keep up appearances, however false those appearances have proven to be. The women will be blamed for the men's sins. Extreme examples are the Sharia law stuff in radicalized cultures. In the end, those rules often reveal themselves to be about control and power over women, which is something Jesus disallowed by his words about not lording it over and not being white-washed tombs, not to mention the rebuke about gnats and camels (https://www.recoveringgrace.org/2012/09/the-subtle-power-of-spiritual-abuse-chapter-12-straining-gnats-swallowing-camels/)

These are repostings . . . of old articles, Aila. You can find my comments in the original article. I just don't want to go another round.

And so that sometimes goes, Sunflower. So to take Anne's response under the intense duress of that situation as a definition of IBLP response on that matter . . . well, it is simply not correct.

Alfred, I can read. I know this is a reposting. Of course you don't want to "go another round" because Bill's teaching is indefensible.

Alfred, man looks on the outward appearance. Why do you defend it? Yes, we understand it, but you defend it. Do you really believe Joy manufactured the "jean thing" just to put Anne in such a bad light (certainly not IBLP!). You appear to presume all of BG's critics are lying and acting maliciously. As one who came into this discussion as a bystander, I find them credible and you desperate to impeach them. You can't hear any of them because you presume they are lying. Him who has hears to hear, let him hear.

Frankly, Alfred, you make me think of the Dufflepud "Boss" in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. Do you have some sycophants around you exclaiming: "Right boss! You really told them what's what!" Do your children read this site and congratulate you on your deconstructions of the "false" accusations?

C. S. Lewis ... portrays the dufflepuds in The Voyage of the "Dawn Treader." These creatures, in their silliness, are extremely loyal to their foolish leader, affirming all he says:

“Well done, Chief. You never said a truer word. You never made a better plan, Chief. You couldn’t have a better plan than that.… Couldn’t have a better order. Just what we were going to say ourselves. Off we go!” (pp. 112, 113).

http://succeedtolead.com/pdfs/articles/ethics/Is_Loyalty_Still_a_Business_Virtue_Whetstone_06_09.pdf

Esbee, I think there was probably a matriarchy in the Gothard family, too. For starters.

Alfred, you said, "Bill told me ..." when you interpreted a story for Esbee. HELLO?? You cannot see anything except through the lenses Bill has instructed you to wear. That's why I feel sooooo sorry for you ... in a pitiful way, not a helpless or innocent way. Because you're neither helpless nor innocent. You need to put on some big boy drawers, LOSE the lenses , and CHOOSE to think for yourself. Your friend has such a grip on you that it makes you awfully bold in defending him ... bold enough to be offensive to Esbee (my opinion - when you said, "are you kidding me?" even though you weren't there .. just instructed what to think about it.)

You're a grown man. It's late, but not too late. Get your empathy on and CHOOSE to look at these stories from another viewpoint ... the story tellers', the minor characters', the bystanders', Jesus', or even just your OWN for once. Anybody's but Bill's or his machine's.

If you've been in "closed fellowships" all your life, I'd have to say that they've done you no favors. (How do you fulfill the Great Commission in those things? I've never understood that part.) There's a whole new world out there if you're willing to start thinking for yourself. If not, the bondage you're in is your choice.

I AM a grown man, Elizabeth . . . I have 11 kids . . . I have lived a lot in 55 years, including 41 with some association with IBLP. I got two of those ungodly degrees Summa Cum Laude and a high school teaching credential. 27 years in the computer industry. But . . . Sounds like you know better than I do, enough to belittle and despise me in public.

And you know nothing about closed fellowships. We preach the Gospel 4-5 times a week in different venues . . . Our people preach at Pacific Garden Mission alone 2-3 times a week to 300-1,000 folks at a time. Great commission is alive and well.

Alfred, Elizabeth made (I think) several good points. I find it interesting that you only really responded to the one about closed fellowships (having nothing to do wigh BG). It seems like to me that you pretend to respond to the others, but it looks like what you are really saying is, "I am smart and grown up and how dare you talk to me that way?"

Once again it looks like you are comfortable with people responding to you with, "“Well done, Chief. You never said a truer word."

While it is true that on the surface perhaps Elizabeth might have used softer words, if one goes back and rereads what she has written to you this last week, it is clear in my mind she has shown considerable restraint. I am guessing that many of us would love to have someone show the love and concern she has shown to you.

I'm sorry that my rebukes come across as despising and belittling. You've been rebuked by people that would just as soon write you off, and I don't blame them; I'm just not one of them. You HAVE been far less than kind or empathetic to people who have taken great risks and poured their hearts out here about how they've been hurt by a man who happens to mean a great deal to you. But what I see under that is a person I can relate to, albeit in a limited way.

I have been under the spell of a master manipulator over half my life. I have been lied to, lied about, mooched from, outright stolen from, conned, used, and abused to a degree I can barely comprehend myself. I've been told - skillfully and imperceptibly - what to think and how to interpret reality. I know their MO, I know how sincere they are, I know how they divert attention, I know how they project their own faults on others. And I especially know how they intricately frame "reality" for others. Their victims aren't stupid, either ... we just feel that way when we figure all this out. :)

Unfortunately, you don't yet see the commonality ... you don't understand why I give a hoot. It's frustrating, but it's okay.

You see me as an adversary. If I were, I could easily ignore you. But as your friend - my assessment, not yours :) - I just feel the need to challenge you straight-on and try to take up for some of the people you offend.

And you're right, I know practically nothing about "closed fellowships," for which I'm very thankful. I was asking an honest question, because I really can't imagine what purpose they serve.

My hope is that you will be able to see truth ... plainly, and FOR YOURSELF. That's what really matters, not whether you like me or understand my intentions.

I'm sorry, I know this is a rabbit trail. But can someone please tell me what a "closed fellowship" is? I have never heard the term except in terms of who may or may not participate in communion at a specific church.

Thanks.

@mosessister: I am not a member of a "closed fellowship" but I think I can tell you what one is. I see that Alfred attends a "gospel hall". That is one way to tell if it's closed but not necessarily. It is commonly one of the groups associated with what is called "Plymouth Brethren". Many gospel halls are closed (but not all so it makes it hard to know). I guess if you went in and were asked to sit in the back you would know you were in a closed fellowship. You might even be asked to leave. I attend a so called Plymouth Brethren fellowship that is very open and doesn't even demand head coverings. Most do wear one but not all. Many women wear slacks and even some wear jeans! I have been to Bible churches that are very like our meeting so it just depends. I don't think Alfred would be comfortable in our PB meeting and I know I wouldn't be comvfortable in his even though I usually wear a head covering and usually dresses although in winter I usually wear slacks. But I doubt if they would let me in anyway. I don't know this for a fact but it seems like there might be more closed fellowships in Europe than in the US. My friend who lives in Germany attends one and after over 50 years they accept her in the meeting but she still does not participate in communion. She can sit in the back and listen and even enjoy meals with them but she has just decided that they are people who love The Lord and she does what she can. In some cases I've known about if one from a closed fellowship came to our open meeting and partookl in the communion he would not be allowed to do so in his closed fellowship because he did it in ours. I suppose if Alfred came to our meeting and partook of communion he would not be allowed back in his for some time. I don't know how that works in every case. Just know that it has happened with someone from Switzerland who fellowshipped with us and knew that he might not be able to back in Switzerland. Just my 2ents worth. I'm happy where we fellowship and the people are loving and accepting of anyone who walks in the door. If they should turn out to be a wolf then they are asked to leave. Hasn't happened very often.

I am getting back to Elizabeth . . . but . . . hats off, Eva. You know a lot.

Yes . . . we have a "closed table", Billy Graham or Bill Gothard would sit in the back and "observe" . . . the morning meeting on Sunday only. Closed fellowships have an acceptance process that includes accepting the basic requirement to not join, attend, have fellowship with other groups. That expectation would include the Mennonite churches, where Tony grew up.

The process of church discipline is practiced along the lines of Matthew 18 . . . if a member is "put out", they are then "shunned" as a heathen man and publican. There are different degrees of this practiced . . . some I have heard of do not even allow a spouse "put out" to eat with their own family.

The process of being "put out" is serious and focused. From the perspective I have gained from being inside such a setting all my life I can tell you that it is jealously guarded from influence from outsiders. Part of the reason is that other groups are regarded with varying degrees of suspicion, even outright rejection . . . as "unclean". That is why one is prohibited from attending them . . . and their authorities are given no honor at all.

If someone came from one of these groups to our Assembly to demand action against one of our members, I am sure it would be listened to. If that action involved proof that they had been violating church rules, that evidence would be used against them. But if it involved matters outside the jurisdiction of the church, it would be basically ignored.

Meaning . . . if Tony went to my elders and complained about my persecuting him or supporting a wicked man like Bill Gothard, my elders would see whether I have been faithful to the Assembly and generally honorable as a believer. If so, they would let him know that those are matters that do not concern them or the church. To put me out, however, would most definitely HAVE to involve an infraction against the Assembly . . . immorality, drunkenness, financial improprieties, attacks on our leadership or members, or having fellowship in other churches.

Which is why the veiled reference to "a technicality" interests me. I just can't imagine what that would be. People do not get shunned - which, in our case, at least, requires a special solemn meeting of the entire group - for "a technicality". A lifelong member, with family there? No . . . way.

Looks like I inadvertently joined two threads I have been posting in. The Tony Guhr comments really belong over in "The Agent" OP. "Closed Fellowships" have been on my mind a lot, I guess . . .

@Eva, thank you for the explanation. I learned something new today!

Elizabeth: "I'm sorry that my rebukes come across as despising and belittling."

You talk a lot, Elizabeth. Do yourself a favor and seriously listen to the "other side". Consider the possibility that Bill may not be quite the unmitigated villain presented, and that I am not a complete idiot, might actually have something worthwhile to ponder.

"But as your friend - my assessment, not yours :) - I just feel the need to challenge you straight-on and try to take up for some of the people you offend."

I appreciate the sentiments, Elizabeth.

I have been around at-Bill-offended people all of my life. You know, back in the day, it was his doctrine, what he taught - rock music, authority, divorce . . . precisely the same anger without any context of wrongdoing. Somehow, whatever it takes, Bill must go. WHY is that? Now, with the power of the Internet, we have dug up all kinds of tidbits to further the cause. And Bill did some really foolishly inappropriate things along the way, enough shrapnel to load into the blunderbuss and hurt him.

Whatever else may be said, it has been amazing how Bill has been able to "bounce back" time and again. It reminds me of a verse . . . "For a just man falleth seven times, and riseth up again: but the wicked shall fall into mischief." (Proverbs 24:16) A fall is a fall . . . David fell . . . Jacob stumbled . . . Noah sinned . . . Abraham was foolish . . . Moses had even his own family complaining . . . Elijah wimped out . . . John the Baptist doubted. In the end, the Lord is judge . . . it is not a majority opinion. If God gives His honor as a vote, in the end that is all that matters.

""closed fellowships," . . . I really can't imagine what purpose they serve."

A family is a "closed fellowship". Not just anyone can walk in your front door on any given day and sit down at your table for a meal. What purpose is that for, assuming you agree with that? Whatever your reasons for barring the door and only openly it to invited guests, well, those are the reasons for a closed church fellowship.

"My hope is that you will be able to see truth ... plainly, and FOR YOURSELF."

That is my cry and prayer. I trust it is yours as well.

I would love to have been a fly on the wall in his house and seen the family dynamics as he was growing up.....some of the things his sisters have said and done (in one story a woman recounts how overly reactive Bill's sister was to seeing her wear jeans) are a clue to the rest of the iceberg of what may be wrong in that family. I wonder if that family wasn't a matriarchy."

I have no doubt, especially after hearing stuff like "the one who's under authority is really the one who has the power" in the seminars.

This comment has been made by many on previous posts on the Parent Recovery page on FB:

" I cannot read Matthew 5, 6 7," or " Romans 6" etc...

This is due to the ingraining, and over studying that came with the Wisdom Booklets. Mix that with an over zealous Husband, Dad, or Mom, some anger and frustration at your kids, not DOING what the Bible says but studying it nonetheless - and you have the makings of a Molotov Cocktail. The end result is many poor memories centered - unfortunately - around the Bible. This grieves me so...

I am very grateful for the parents that have spoken up and been so vulnerable and honest about his. It is not easy as a Christian to admit you do not read the Bible or that parts of it are a "no go" due to bad memories. Some have even said they have VERY adverse reactions to certain parts of God's precious Word. Flashback type things.

This site and the revelations of student and parent alike on the FB pages related to ATI have all helped me so much in my desire to understand my children and not write them off as "rebels" (the go-to word for most staunch ATI parents and many a church). I have such a desire to discuss these things with them and wait patiently for those times to present themselves (and they have and do).

We were in ATI for 11 years - very developmental years - and ATI was in us longer than that. I recognized the photo in this article immediately. I had taught it. Now looking at it and reading the comments, I could not agree more. Such a rabbit trail (and a dishonest one) in the Wisdom Booklet. Thankfully I still love the Beatitudes and have heard many a godly man and woman speak on them.

Our children were 9,7,5,4 when we joined ATI. They are now 30,28,26,24. And God gave us one 11 years ago who was so little he does not know ATI at all.

Thank you for your article, Kevin. Thank you for caring even though you were not in ATI. Thank you for being understanding to your wife and her reactions to certain things.

And Bev, I always like your comments on RG :) Wish there were 'like' buttons.

The notion that the guideline of modesty must be expressed in 20th century culturally-bound rules dictating women wear dresses and men wear pants is rank nonsense. Everyone knows the ancient Israelite men wore dresses. Ex 20:26. And you shall not go up by steps to My altar, so that your nakedness will not be exposed on it. LOL.

Great article, Kevin.

AGREE!!!! Why don't some people "get it.

?"

Wasn't this suppose to be about how Gothardism takes different passages like the Beatituds and twists them into something they are not about like women's clothes. I am not sure how women wearing pants or not matters here. What this article is about is twisting the meaning of a beautiful Bible passage and what Jesus was teaching into something that it doesn't was which obscures what Jesus was actually teaching. I really don't think Jesus cares as much whether I wear pants or jeans or not but that I try to follow Him in living a moral life and it is morality that got Steve and Bill Gothard in trouble. Not the clothes they wore.

Thanks for bringing us back to topic, rob war.

1. The lacy bodice

2. The pattern on the skirt

3. The frayed bottom part of the collar

4. The slit

5. The excessive fabric accentuating the cleavage

6. The patterned tights

Yeah, this had me going for quite the long time. I was the epitome of frumpy-dumpy. :/ However, I'm free now!!!

I think Matthew made some great points in his above comment about how women are treated in Christian communities where there is a strict no pants etc type code and in keeping with the current topic, how women dress has nothing to do with what Jesus was saying in the Beatitudes. I also find it rather curious that Bill Gothard rarely references how Jesus treated women and interacted with them as recorded in scripture. The classic women caught in adultery very much highlights the blame the woman mentality that Gothard promotes. He is in more in line with Islam than Jesus who simple told her "go and sin no more". Jesus talk with women, interacted with them, treated them as equals. I am always curious when different Churches get hung up on a dress code yet seem to ignore James when he mentioned about how to treat others if they come to Church dressed poorly. James admonished that someone dressed poorly should be treated equally to someone dressed nicely. Alfred, you again seem to play right into the post it over the masterpiece like your mentor Bill Gothard. I am curious if you have any substantial comment on the actual Beatitudes instead of going off about women in pants as if that would be considered a "mortal" sin. Well, adultery is usually considered either deadly or "mortal" in some Churches not women wearing pants. In the sermon on the mount, Jesus did mention that if a man even "looks" at a woman with lust, he has committed adultery. Jesus didn't mention that the woman are to blame by what they wear. Sin comes from the inside of man not the outside. Read the whole Matthew 5-7. What people are wearing is never mentioned. What is in one's heart matters a whole lot more. Alfred, you are a true son of your spiritual father Bill Gothard. I think it is sad for you really.

How different would teaching about attire be if it were directed at men learning to not be "trapped" rather than directed at women not trapping. When I see a woman dressed very immodestly, I can see someone out to "get" me (or "get something"), or I can see someone who might be needy for love or attention who needs to know that Jesus will love her as she needs and also needs to know that no man attracted by her dress is worthy of her. It's my heart response that matters to Jesus, not her attire. Heck, Jesus made her NAKED!

Jesus wore robes, not pants. Why do men today get to wear pants?

You're so funny, Don! Imagine Gothardism teaching men something about their heart conditions! Like Dee pointed out above, Gothardism's only instruction for men has to do with asserting authority. As long as a man claims and wields ample authority, there's practically no wrong he can do. [Gag.]

When you contemplate (really stop and think about!) the theme that is woven through all his teaching ... the absolute hatred of women (am I right?) ... it's all rather sickening. It also tends to make one wonder what Bill's childhood was like.

Seems to me that in these closed communities, the men make the rules and so they get to look reasonable normal but the women have to look weird. Of course weird often means that if it was 50 or 100 years ago they would be in high fashion, which then would have been worldly, right? And abusers are known to want to isolate their victims. Strange clothes help so much with that. And then as I've said before, the dress thing is a lot about easy access. How could you play footsies/legsies, etc. very well if your target wears pants? They are too modest maybe? See, depends on your thought pattern, God doesn't look on the outward appearance. Oh, does it really say that in scripture?

Checking in on this site as I do from time to time, it amazes me that "The Cheerleader" (aka Mr. C.) still finds voice to respond to the truths that have been logically, patiently presented to him for months on end. I would think that someone who has such experience dealing with children would instantly recognize the attention-getting ploy like "The Final Word" game that he himself has been excercising, ad infinitum. However, I suppose that some are patently resistant to becoming grown-ups, their physical age notwithstanding.

I recall as an 11 year-old complaining to my parents on long car trips that my little sister was incessantly "bugging" me, and being told that simply ignoring her would divert her attention to something else. Sure enough, as soon as I realized that not reacting to her "got you last" tags was an effective way to shut down her energy, the more quickly I did it the next time. I was also the youthful pest in other scenarios growing up, but realized early enough in life that others would turn their backs to me if I continued that way.

As RC's noteworthy contributors have tried reasoning with The Cheerleader in shows of tolerance that would sorely test Job - with the outcome remaining the same (if not worse, as no learning, or recognition of facts ever seems to take place), I wonder whether allowing his pedantic diatribes to go unresponded to might eventually bring the desired results. That he'll also read this and possibly reply to it is also a possibility, but there comes a time in every godly adult's life in which s/he needs to serve as the example, and not an intentional continuation of the problem.

If the latter situation persists, especially as it could easily be considered nothing more than a highly annoying form of agitation, it might be best to consider his future comments invisible, with readers moving on to the next line. We put kids in 'time-out' all the time for similar infractions, with I daresay much more encouraging progress. Just my two-cents' worth.

Jerrod,

I think your two cents are valid. However I also think that Alfred's continued defense of BG accomplishes at least three things. 1) For new visitors to this site he demonstrates the absolute control Bill has wielded over individuals who followed him so closely, by his own admission he has been involved at some level his entire adult life. 2) His continuing inability to recognize the harm Bill has caused, reinforces the idea of IBLP legalism which values performance and appearance over loving concern for others and servant hood that Christ modeled. 3) His comments give others the opportunity to articulate opposing views which may help those struggling to overcome the lingering effects of Gothardism which has affected many who peruse this site. I've had the same thoughts that you expressed, why encourage him? But then I realized he's actually helping the "other side" and he doesn't even realize it.

What Aila said.

good thoughts, Jerrod. For my part, I do usually try to avoid getting drug back into it. Once in a while, there is a comment I can't resist making. But even then, it's probably just as likely I'm contributing to heat more than light.

Matthew - I appreciate your chime-in, and commend you for both withholding your comments, as well as making them, as you feel it's appropriate. I'd be quite tempted myself to reply directly to He-Who-Shall-Not-Be-Named, but like you and no doubt others, I don't wish to rekindle a fire we just wish would extinguish itself once and for all. Well done on the biblically-based, clear-minded feedback, and I'll be watching from the wings, as this relevant discussion continues. :)

Aila - thanks for the quick and insightful follow-up, which constitute very good points to make (especially, as you rightly say, for those reading this site for the first time). For the record, I've considered the retorts to Alfred's tired arguments to be very strong and purposeful, and for the reasons you've cited, I'm heartened that so many have expressed their views on the harm that BG/IBLP have inflicted on them personally, on family members, or others they know.

As we often hear about in Gothardism, those affected parents are given to believe that they should treat their adult children as youngsters for as long as it pleases them. When I wrote the comments above, I wondered whether the self-proclaimed adult in the room might be interested in knowing how it felt to be infantalized himself for once, and decided to leave the wording the way that it was.

I appreciate your contributions, as well as those of many others who've been through the wringer, and are doing their utmost to ensure that no one else will ever have to, if they have anything to do with it. That said, "bravo!" to this brave cadre of overcomers, and may victory ultimately prevail on these pages.

Jerrod,

I believe it was entirely appropriate for you to point out Alfred's behavior. It appears that he desperately wants attention, when people respond to his comments he feels validated. We all have degrees, accomplishments, accolades and achievements that we could list, but to what purpose? To lord it over someone else? "This is what The Lord says: "let not the wise man boast of his wisdom, or the strong man boast of his strength, or the rich man boast of his riches, but let him who boasts, boast about this that he understands and knows me, that I am The Lord who exercises kindness and justice, and righteousness on earth, for in these I delight," declares The Lord. ". Jeremiah 9:23-24. Unfortunately, Bill built his empire around his interpretations of wisdom, the strength found in large numbers of followers, and the money that flowed from his programs. Now it is all falling apart, and there are those who are desperately trying to save it. As an observer, I can't fathom what is worth saving.

Alia - I completely concur, and have been pleased to review evidence that so many caught up in this rancid system have 'seen the light', as further proof unfolds. Their testimonies - unlike some - are born of humility and new-found wisdom (meaning real, divinely-wrought wisdom, vs. a mimicry of the eponymous booklets, described throughout these chapters), and are a joy to read. Here's praying that even the most recalicitrant among RG's commentators will experience similar revelations in the days ahead, as God's blessed hope and redemption are meant for all.

On one level,Bill Gothard could be somewhat defended by admitting that his doctrines,belief systems,and theology,need changed,as though a mental apprehension,of his mistakes is all it takes,and in a politically posturing way,he seemed to have done that;this to the somewhat satisfying of many supporters.On another level, with Heather's Story,Charlotte's Story,Ruth'sStory,the dark side of wickedness can't be understood;The forcing of Heather to care for Bill's mother,without food.Constant confessions of deeds,not committed by Heather to avoid psychological anguish from constant interrogations at the Indy Training Center.Demands.Finally being honest about liking a guy,and her reward for being honest?Solitary Confinement.Being called a whore.Blackmail.All with a calculated end an utterly ruthless disregard for any effects upon the young teenage girls psyche,which she now states left her with numerous inner wounds Gothard to this day most callously has never avowed.Along with "no crimes were ever committed" by him in the evaluation from the board of directors.This is another level,and the more darkly inhumane,the less supporters can face its damage inflicted,and the less those who oppose can imagine and take in the scope of purposely inflcted pain on hapless lambs.A darker,subliminal level of tyranny,control,and exploitation,waiting for another "oppertunity"For the sake of these lambs,their stories should ever be trivialised for the sake of the tyrant behind the program,the weakest of these voices should never be squelched.Give them eloquence,compassion,sympathy,hope,from the "business as usual"man .

For people to move beyond the post it notes and look at the real art, one has to start removing the post it notes. The best way to do this is to start asking

the objective hard questions concerning the ATI curriculum. Is it really reasonable to base a K -12 homeschool curriculum on the Beatitudes? Is that the proper use of Matthew 5? Does trying to fill this kind of school program lead to the extrapolation that we see here and the results are a rather unBiblical use and interpretation and application? Did Bill Gothard use credible theologians to come up with this or did he just rely on his own fasting, reading and memorizing? Did Bill Gothard ever double check his material against other historic Christian groups and understanding? Did Bill basing ATI on Matthew 5, ignore Matthew 6 and 7 (and the rest of the Bible)?

Did basing ATI program on just Matthew 5 lead to a stunted homeschool program? These are the questions that need to be asked not if women should be wearing pants. These types of questions go to the heart of the issue of Bill Gothard's teaching. Maybe if more pastors asked these types of questions instead of going along

for the ride and encouraging others to attend, there wouldn't be the type of confusion that is seen here.

rob,

Thanks for asking the pertinent questions. As a parent who has homeschooled all of my children for part of their education, I organized literature seminars for high school students, field trips to historic sites, first person history classes with interesting speakers, art classes, service projects etc. These were to supplement a solid curriculum. The activities described in the article do not seem adequate to me to base a high school curriculum upon. Perhaps Bill knew this too, and that is why he discouraged higher education. Having students trying to start college who weren't prepared would have not looked good at all.

When I've read the articles describing ATI curriculum, that the students were to go through twice in the K-12 time frame, it made no sense to me. Thank you Kevin for explaining it. The one time I saw the Duggar TV show, a bunch of kids were sitting around a table for their homeschooling time. I couldn't figure it out, no books, workbooks, paper or pencils. What was Michelle doing? Now I guess I know . . . no wonder there are so many people who look down on homeschooling. The program just seems like a way to keep a base of supporters and an income stream. I only experienced Gothard from a distance, had friends that attended seminars, I never knew until I came across this site the number of people who were exposed to his teachings through home schooling.

Excellent questions - I can answer the last one from experience. First of all, the Wisdom Booklet series did go through all of Matthew 5, 6, & 7. Each of the 54 Booklets took on or two verses from the chapters (moving in chronological order) and based studies in Greek, language, history, law, medicine, and science on whatever theme seemed to be in the verse. For example, the passages in Matthew 7 about knowing teachers by their fruits had science sections on pruning fruit trees and how to identify quality fruits in the grocery store. My family spent nearly 10 years in the program and we went through the 54 booklets about one and half times.

Not only were there no grades, but subjects came and went as the writers of the booklets perceived connections to the verses. I remember studying logarithms as a preteen - understanding very little of it - simply because there was an apparent connection between trigonometry and the verse that was the topic of the current Wisdom Booklet. As a result, my education became a piecemeal of random facts. Some were not true, like the science resource that claimed that the gospel was written in the name meanings of the constellations (this has been refuted even by such conservative groups as the Institute for Creation Research). By the time I reached 18, I was very uncertain of what topics I had or had not studied.

My homeschooling parents had joined the program on the assurance that ATI was a good alternative to conventional high school studies for their family of young teens (my mother had given us an excellent foundation in the lower grades). My parents did try to provide supplemental materials to ensure that we learned grammar, math, history, and science, but our time was so taken up with projects from the Wisdom Booklets that my other studies were very sporadic. The things that kept me from being completely ignorant were a family that encouraged curiosity, a passion for reading anything (even the encyclopedia), and music lessons from a private teacher.

I managed to write the GED from my scattered learning and attend a community college for nursing. Sadly, my great desire to study medicine could not be fulfilled, because I had no high school credits; though many of my teachers and my coworkers have told me that I could/should have become a physician. I have done aid work as a nurse but, working in an area where there were no doctors, I was daily reminded of the lost years I spent groping in the educational mist that was ATI.

Quiet One, I am sorry to hear that you weren't able to realize your desire to study medicine. Might I encourage you that it is never too late? A high MCAT score counts for a great deal, as will your existing nursing experience. I counseled a young person in my former church, also homeschooled in ATI and GED only, to focus on getting the highest MCAT score possible; after a couple of tries he gained admittance to med school and is now a practicing physician. D.O. schools, in my experience, accept a more diverse group of students than do M.D. schools, and you might not be able to get into a research-focused program, but there are still plenty of other options. If you are interested in practicing in a rural or impoverished area so much the better, as many public med schools are tasked by their state legislature with trying to increase the number of physicians to underserved populations, and a clear commitment in that regard will not only help your admittance chances, but also may get your schooling paid for. Med school is expensive but if you have shed the Gothardite fear of debt, you will find legitimate companies happy to give a future physician a loan. Age doesn't matter; it is not uncommon for med school classes to have students in their forties and I have even known one in her sixties! Your contributions to this site are always intelligent and well-written; you can absolutely handle med school. If that's still what you desire, don't give up.

Quiet One, I just realized from your comment below that you are outside the US! So my med school advice likely doesn't apply at all. But I hope you will continue to pursue the desire of your heart.

P.L. - Thank you for your kind words of encouragement. I do still trust in God and I have a certainty that He does work everything out for good. The post-ATI years have been a wild, but wonderful, ride with my Lord. I do keep a small flame burning for medical school; although I am too mentally, physically, and financially exhausted to try for it just now.

Quite one, never give up on your dreams or desire. Pl gave excellent advice and beat me to the punch. If you can focus on taking the MCAT and doing well on that test, there might openings for you even out of the country. I want to highly encourage you. Can you continue to work on the RN?

Rob, I think something may be misunderstood. The approach of the Wisdom Booklets, as The Quiet One shows, was to use topics in the month's scripture passage as jumping off points for academic studies. Educators do this with movies, current events, stories and all kinds of sources. It is a way to explore "random facts" based on a connection with something interesting. It is distinct from systematic studies of topics independently. But a unit on the human eye, taken from a verse like Matt. 5:1 ("seeing the multitude...") would not purport to be explaining or interpreting the verse, but just a convenient segue to a topic. The bad teaching was all the Gothardism that was forced into the multitude of topics, including sloppy scholarship, reliance on anecdotal information, etc.

Now that I think about it, the approach devalued Scripture because it used Scripture for a secondary purpose: finding issues and topics to study apart from the Spirit's purpose in the text. Of course, since BG built his entire program on the misuse of Scripture to proof-text his peculiar convictions, it should not surprise us that he would use Scripture to do anything. He may even use it as a Ouija Board!

I do not regret the topical approach to curriculum. I do not regret the bible memory or the diagraming of scriptural sentences. I do regret the indoctrination of legalism and self-righteousness that affected my children in ways we are just beginning to discover. I deeply regret my neglect of my wife in not sharing the ATI burden with her. I deeply regret that my children have had scarce marriage opportunities in their 20's and I fear that ATI and the Seminars exacerbated the defects in our approach that brought this sorrow.

On the academic side, while we supplemented with Easy Grammar and Saxon Math, all my children earned college scholarships and could have studied anything they wished. (I have a law degree and my wife has a Bachelors Degree; parental background often affects offspring academic opportunities regardless of school setting.) So I do not blame the Wisdom Booklets for depriving mine of useful knowledge. It's the false teachings and human wisdom that were potentially damaging, not the topical science, history and economics.

It is my understanding that ATI students in the US were often able to gain credits for college using the SAT or AP exams. However, that option was not available in my country. Thus, ATI's topical curriculum and discouragement of the grading system proved very damaging to my siblings and I in our educational options.

It may have been possible for gain credits for college, but in my experience, college was discouraged. Emphasis was placed on experience gained through service to God [translation: work at a training center]. My parents have college degrees, but I was never led to believe that I would be allowed to go. In fact, I was told that was not appropriate for me and would not be coming to fruition. In addition, the English class I took online never transferred to any of the colleges to which I attempted to transfer it. For me, while there were a few bleak doors to higher education, they were difficult to make happen and highly discouraged by all the authorities in my life. It was like being a hamster on a wheel... in a cage.

Back in the bad old days of ATIA, college was constantly referred to as a "high place" and was explicitly called idolatry. It was actively discouraged.

A semi-rhetorical question occurs to me - with college being referred to as a "high place" and called idolatry and discouraged - maybe was the thought that students' exposure to different ideas / critical thinking in a college environment might cause the IBLP control / ATIA empire to implode?? Sad.

Yes, I did go along for a while with ATI's condemnation of college (I kept hoping that ATI's promised medical program might actually happen). However, my parents weren't the ones who discouraged me - they encouraged me to follow where I felt called to go. In my teen years, when most children go through a period of thinking they know more than their parents, my form of mental superiority was to swallow everything ATI taught (as I said, I read everything) and think my parents would never know real success unless they did likewise. Looking back, I am struck with the bitter irony of it all. The part of me that wanted to learn to help and serve others was crushed, because that way involved violating ATI standards; while the part of me that was self-satisfied and scornful of others' inferior standards was encouraged because I was an ATI apprenticeship student, one of "the best of the best".

Brumby, I know exactly what you mean by feeling like a hamster on a wheel - I spent nearly a decade after ATI just getting the education I that do have.

Great comments. But, no, Becoming, the honest view of most ATI parents who opposed college was that it was !!DANGEROUS!!. It was fear of corruption, not fear of exposing the deficiencies of ATI, etc. And I truly believe that Gothard believed he could build up an alternative structure that would be better. He. Just. Failed.

His ideas about apprenticeship were very wonderful--they just never expanded far outside the ATI/HQ/TC environment because the man was a control-freak and could NOT let anyone else influence anything unless they were a BG sycophant.

HAD we all apprenticed young people in our various REAL trades and professions (the ones paying for all the programming), today they would be more gainfully employed and more confident in their abilities and talents. BUT, the idea of apprenticeship dissolved beyond the walls of ATI/family control and thus became fruitless as a movement.

I have, in fact, had the privilege of working with a small number of ATI students, lacking in college education, in the Florida Legislature, thanks to Dan Webster's influence. Some of them, following their calling in public service, have gone on to get undergraduate degrees and law degrees. One of them is now my boss, Chief of Staff of the Florida House of Representatives! But none of these young people made decisions based on fear. All found the mentors and examples they needed to help them become godly professionals.

But those trapped in the inward-focused ATI culture could not find such opportunity without completely escaping.

Ask yourself: how many leaders did Bill Gothard raise up in 40 years? Ask yourself: what men did he train to carry on after he was gone? By this I conclude that he was, maliciously or foolishly, about control and self, not about the welfare of those he claimed to serve. His view of "success" was submission rather than fruitfulness. "Islam" means "submission".

Thanks, Don, for your detailed explanation of the background of the anti-college view. I agree - it's too bad the apprenticeship program didn't come to fruition either - a society definitely needs good car mechanics and good tradesmen! :-) So sad.

I'm really glad you've been able to help a small number of ATI students, and I'm glad Dan Webster's been on board as well. (Was he in the legislature before he became a congressman?)

You said, "Ask yourself: how many leaders did Bill Gothard raise up in 40 years? Ask yourself: what men did he train to carry on after he was gone? By this I conclude that he was, maliciously or foolishly, about control and self, not about the welfare of those he claimed to serve. His view of "success" was submission rather than fruitfulness." Excellent point!

IMO, how incredibly sad a legacy he will leave. Repentance would certainly help him personally, and might help resolve some issues between himself and individuals (should he ever repent). However, even with a (potential) repentance, the fallout of 40 years of "all of the above" that's been part and parcel of his system has so damaged SO many people – even those who were never involved with him personally (at headquarters etc.) or never interacted with him at any personal level (such as those who only viewed video seminar(s)). His repentance – anyone’s actually, I suspect, under any circumstances – may help heal people from damage but I don’t think it unwinds the consequences of the wrong actions. Moving forward in freedom is possible, but what a shame that such a bad, legalistic system was created – especially if, perhaps, it was in response to his unresolved personal issues (perhaps a matriarchy in his family of origin? as a couple of people have suggested).

Becoming Free, your comment about repentance being unable to unwind the consequences of wrong actions reminded me of this idea:

"Grace will remake but not undo. There is all the difference in the world between Christ uncrucified and Christ risen: they speak of two different hopes for humanity, one unrealizable, the other barely imaginable but at least truthful." ~Rowan Williams

Thank don, you gav some incredible insights into the structure of ati which looks to be more of a deficient system of education. Saxon math (and phonics) is a very good program, my daughter had that in the charter school she attended. Your children seem to have done well due to you and your wife supplementing the weaknesses of at which is really at the heart of any education system, parents meeting the needs of their children and helping them. I am more curious now in the setup which is not a systematic education system which topics build on themselves through the years but topical. Most education is systematically based. Topical is very usual for a k to 12 and I wonder if this based on bill's own struggles in his early years and how he actually learned which was by memorizing and topical. It almost appears as if bill built this homeschooling programs based on how he learns. Did he even consult other educators in the set up? Sometimes the hardest person to forgive is oneself. Even though you have regret, don't beat yourself up over them it sounds like you worked to get your children ahead doing others things and are on the mend moving forward not backwards. God bless

Thanks. You insights on BG's memorization emphasis make sense. I know that my own struggles in K-5 motivated me to homeschool my children. Most boys simply are not ready to sit in straight little rows when they are 6! Most American boys starting school after WWII had similar frustrations. John Taylor Gatto wrote about this in "Dumbing Us Down".

Others beside ATI have tried the topical approach. Montessori is very different from the structure that typical schools use. There are all kinds of "innovations" out there and BG grabbed some that made sense to him and ran with them. Some approaches are fruitful for some students, others for other students. Phonics is "better" for most, but not all. Etc.

I don't fault ATI for trying the topical approach. It was especially beneficial in the mixed-age settings for which the program was intended. I fault ATI for not being more attentive to fruit and truth! The only ATI personnel who ever inquired into our actual successes were like 19-year old "Family Coordinators". What nonsense!

In our ati years (1985-1998 - it takes some of us longer to discern error! -) there were several really good "educators" who gave some good stuff...however, as I understand it, they were under the extreme controlling hand of BG and not allowed to structure things the way they knew to, and thus they left and got involved in homeschooling under their own name and ideas - a wise decision for them, ,but a loss for ATI...It was after one of the best educators I had heard in the program left that the decision was made to completely start over with the Wisdom Booklets due to some "errors" that initially made the program , should I say, impossible...like completing one Wisdom booklet and all the extra studies with it in 2 weeks. We had just finished a year of rushing through them (with a 3 and 5 year old) and in addition, because there were no parent guides, we had to write out everything we did to teach the lessons and send it in with our reports...thus the parent guides were born...and MUCH of them was the hard work of parents in the program who thought up and implemented the ideas for hands-on things. It was a nightmare. I should have known then. It seemed that every year there was a "new" amazing proposition of a program or idea that would make it even better, but each year, that was the last you heard of it...you tried to implement it and the next year it was never spoken of again. In short, there probably were many educators consulted, but they had to submit to control and not being allowed to make a move that hadn't been pre-approved at the top. I am sure it was stifling to try and accomplish any good changes working on that team.

HSLDA warns of the dangerous teachings of Bill Gothard and Doug Phillips.

Bravo HSLDA! Most of my friends who still cling to IBLP have a great deal of respect for HSLDA. I expect that this will get the attention of many people:

http://hslda.org/courtreport/V30N2/V30N202.asp

"What has changed our minds are the stories we are now hearing of families, children, women, and even fathers who have been harmed by these philosophies. While these stories represent a small minority of homeschoolers, we can see a discernible pattern of harm, and it must be addressed."

"Gothard’s teaching is also unbalanced regarding family relationships and the treatment of women, but he does not specifically promote the patriarchy movement. Rather, it would be more accurate to describe his teaching as legalism. In this sense, legalism occurs when someone elevates his personal view about wise conduct to a level where it is claimed that this person’s own opinions are God’s universal commands. It is not wrong to have personal opinions. What is wrong is to usurp the role of God."

"People are misled when human ideas are wrapped in false claims of being God’s directives. Different forms of critical analysis are necessary when one is examining God’s words versus man’s words. Innocent people follow teachers in good faith thinking they are following God. And when the directives turn out to be only man’s ideas, the followers often find that someone in their family has been damaged in the process. Only God’s ideas are infallible. Man’s ideas will always fall short."

Yes, yes, that's it! It is wrong to usurp the role of God and teach your personal opinion as if it is the word of God. Well done and thank you again HSLDA!

Kevin thanks for the link to the HSLDA article. I am so glad they are speaking out. I've wondered about their views on these groups in the past. As an HSLDA member, I know the organization carries a great deal of weight in the homeschool community.

Ooooh, I'll play:

1) Lace is a poor choice for anything but Grandma's kitchen curtains; everyone knows it's itchy.

2) Poor pattern mixing. While it's desirable to combine a larger print with a smaller print, there is not enough contrast here. Next time, perhaps a nice small dot print or thin stripe with that Aztec skirt?

3) Lawd, honey! We've lost you under that enormous collar. A simple sundress will do.

4) Bunchy and Shapeless. If you're going to wear an a-line skirt, at least make sure it's not two sizes too big.

5) Excessive fabric. You're drowning in that heavy sweater and long ill-fitting skirt. To balance this top-heavy look, you should opt for a nice pair of skinny jeans in a dark wash.

6) Complete lack of accessories. Count 'em before you leave the house. Necklace, earrings, bracelets. You've got some work to do.

As an aside, it was not until I started watching What Not to Wear that I learned it's OK for your clothes to actually touch your body. You don't need to swim in them.

I was thinking that all these eyetraps could be resolved with some good dangly earrings to frame the countenance.